8 Authors Who Created Literary Masterpieces Keeping Their Day Jobs

Are you typing away at that manuscript in stolen moments between meetings? Scribbling notes for your novel during your lunch break? Dreaming of the day you can finally quit your day job and write full-time? Here’s a plot twist for you: you might be following in the footsteps of some of the greatest literary minds in history without even realizing it. That cubicle or classroom where you spend your days? It could be the unlikely birthplace of the next literary masterpiece—just as it was for these legendary authors.

The image is as romantic as it is pervasive: a writer in a sun-dappled cabin or book-lined study, spending languid days crafting perfect sentences, unbothered by mundane concerns like meeting payroll deadlines or attending staff meetings. But for most authors—even some of the greatest literary minds in history—this idealized version of the writing life remains firmly in the realm of fantasy.

The truth? Many of literature’s most celebrated masterpieces were written in the shadows of nine-to-five jobs, during predawn hours before commutes, on lunch breaks, or in exhausted evening sessions after children were finally asleep. These weren’t moments of leisurely creation but hard-won battles for time and mental space, squeezed into lives already full with professional obligations.

T.S. Eliot revolutionized poetry while processing foreign accounts at a London bank. Toni Morrison wrote her debut novel before sunrise, then headed to her day job as an editor. Franz Kafka captured the nightmare of modern bureaucracy after spending his days working within one. These weren’t writers who succeeded despite their day jobs—in many cases, these seemingly ordinary careers provided both the financial stability to write without commercial pressure and the real-world experiences that enriched their literary perspectives.

In the stories that follow, you’ll find not just literary history but practical inspiration. For anyone who has ever stared at a blank page after an exhausting workday, wondering if it’s even possible to create something meaningful within the constraints of a busy life, these authors offer a resounding answer: not only is it possible, but some of the world’s most enduring literature has emerged from precisely these challenging circumstances.

T.S. Eliot: Bank Clerk by Day, Poetic Revolutionary by Night

In the foreign transactions department of Lloyd’s Bank in London, a meticulous employee processed colonial accounts, managing currency exchanges with mathematical precision. His colleagues knew him as a capable, if somewhat reserved, banking professional. Few realized they were working alongside the man who would revolutionize 20th-century poetry.

In the foreign transactions department of Lloyd’s Bank in London, a meticulous employee processed colonial accounts, managing currency exchanges with mathematical precision. His colleagues knew him as a capable, if somewhat reserved, banking professional. Few realized they were working alongside the man who would revolutionize 20th-century poetry.

From 1917 to 1925, T.S. Eliot maintained his position at Lloyd’s while simultaneously reshaping the landscape of modern literature. It was during these banking years that Eliot wrote and published “The Waste Land” (1922), a work so groundbreaking that it would permanently alter the course of poetry. The juxtaposition is striking—Eliot’s revolutionary, fragmented masterpiece emerging from the ordered world of banking ledgers and financial transactions.

While his contemporaries might have imagined the poet hunched over manuscripts in bohemian cafés, the reality found Eliot rushing home from the bank to write late into the evening, often working through bouts of exhaustion and ill health. The demanding schedule took its toll; Eliot suffered a nervous breakdown during this period and wrote portions of “The Waste Land” while on medical leave.

Interestingly, Eliot’s immersion in financial systems provided unexpected fodder for his poetic vision. His understanding of economic networks and global financial flows informed his poetry’s intricate structure and international scope. The fragmentation and complexity of modern life—a central theme in “The Waste Land”—mirrored the increasingly interconnected yet disjointed global economy he witnessed daily at Lloyd’s.

Eliot himself acknowledged this unusual duality with characteristic dry wit: “My work at the bank was great experience, gave me a different point of view; different from university people, writers, journalists, or businessmen, and a certain amount of financial acumen, and knowledge of foreign countries.” Later, reflecting on this period, he added, “I should say that it’s just as well for a poet not to live on poetry. It’s perhaps best for him to have a job doing something else.”

The poet’s banking career offered not just financial stability but a critical distance from purely literary circles—a vantage point that allowed him to create work of startling originality while his feet remained planted in the practical world of commerce and exchange.

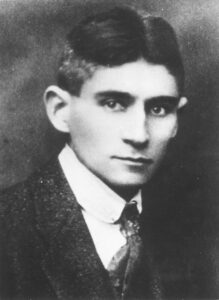

Franz Kafka: Insurance Officer and Literary Genius

By day, Franz Kafka occupied a desk at the Worker’s Accident Insurance Institute in Prague, where he investigated industrial accidents and determined compensation amounts for workers who had lost fingers, limbs, and sometimes lives to machinery. His reports were praised for their clarity and precision—a stark contrast to the surreal, disorienting worlds he created in his fiction after hours.

From 1908 until his early retirement due to tuberculosis in 1922, Kafka maintained this double life. He was no minor functionary; he ascended to the role of chief legal secretary, drafting accident prevention measures for factories and advocating for improved safety standards. His colleagues described him as conscientious and reserved—never suspecting that by night, he was chronicling the nightmarish absurdity of the modern bureaucratic experience.

From 1908 until his early retirement due to tuberculosis in 1922, Kafka maintained this double life. He was no minor functionary; he ascended to the role of chief legal secretary, drafting accident prevention measures for factories and advocating for improved safety standards. His colleagues described him as conscientious and reserved—never suspecting that by night, he was chronicling the nightmarish absurdity of the modern bureaucratic experience.

The parallels between Kafka’s day job and literary obsessions are impossible to ignore. In “The Trial,” protagonist Josef K. faces an impenetrable legal system with incomprehensible rules—mirroring the bewildering insurance claim processes Kafka administered daily. “The Castle” depicts a land surveyor’s futile attempts to reach local authorities, reflecting the institutional barriers Kafka witnessed workers encounter when seeking compensation. Even “The Metamorphosis” can be read as an extreme version of the alienation felt by injured workers suddenly unable to perform their functions in society.

Kafka’s writing routine was as demanding as it was necessary. After dinner with his family, he would sleep for several hours, then rise at 11 PM to write through the night until 2 or 3 AM—sometimes continuing until morning if inspiration struck. He would then return to bed for a few hours before beginning his workday at the insurance office. This punishing schedule contributed to his poor health but created the necessary separation between his public and creative lives.

“Time is short, my strength is limited, the office is a horror, the apartment is noisy,” Kafka wrote in his diary, “and if a pleasant, straightforward life is not possible, then one must try to wriggle through by subtle maneuvers.” These “subtle maneuvers” produced some of literature’s most profound explorations of alienation, bureaucratic absurdity, and existential dread—all written by a man who spent his days processing insurance claims and drafting workplace safety regulations.

Perhaps most poignantly, Kafka never witnessed his own literary immortality. Publishing little during his lifetime, he famously instructed his friend Max Brod to burn his unpublished manuscripts upon his death—an instruction Brod fortunately disobeyed, preserving the nightmarish visions that emerged from the otherwise orderly life of an insurance official.

Toni Morrison: Editor by Day, Novelist Before Dawn

Long before she became a Nobel Prize-winning author, Toni Morrison was already shaping American literature—just from the other side of the publishing desk. As a senior editor at Random House from 1967 to 1983, Morrison championed Black voices and helped bring works by Muhammad Ali, Angela Davis, and Gayl Jones to publication. Few of her colleagues suspected that their accomplished editor was quietly crafting her own literary masterpiece in the predawn darkness of her New York apartment.

Morrison’s writing schedule defied human limits. A single mother raising two young sons, she would wake at 4 AM, make coffee, and write in the quiet stillness before her children stirred. “I always get up and make a cup of coffee while it is still dark—it must be dark—and then I drink the coffee and watch the light come,” she later explained. This ritual preceded long days at Random House, where she edited manuscripts until evening, then returned home for dinner, homework supervision, and bedtime stories.

It was during these stolen morning hours that “The Bluest Eye” took shape—a novel that would challenge America’s ideas about beauty, race, and childhood. Published in 1970, this debut work emerged not from a life of literary leisure but from a tightly scheduled existence where writing had to compete with professional demands and maternal responsibilities.

Morrison’s dual identity as both editor and writer gave her a unique perspective on her own work. Her editorial eye made her ruthlessly efficient with her writing time—she knew exactly what worked and what didn’t. “I would never write the way I do if I had not been an editor,” Morrison once reflected. “Editing taught me what not to do, what was missing and how to fill it, what was excessive and how to trim it.”

Perhaps most significantly, Morrison’s position in publishing revealed the gaps in American literature that her own writing would later fill. Working with manuscripts day after day, she recognized what was missing from the literary landscape: “I wrote my first novel because I wanted to read it,” she famously stated. The stories about Black girlhood, family dynamics, and interior lives that Morrison couldn’t find on bookstore shelves, she ultimately created herself—during those precious morning hours before the rest of the world demanded her attention.

Morrison’s career trajectory offers a powerful reminder that the path to literary greatness rarely follows a straight line. Her Pulitzer Prize, National Book Critics Circle Award, and Nobel Prize in Literature all grew from manuscripts written in the margins of an already full life—proving that sometimes, the most revolutionary art emerges not from unfettered creative freedom, but from the focused intensity of limited time.

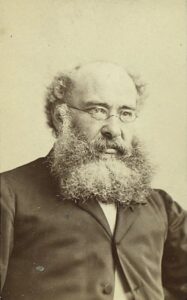

Anthony Trollope: Post Office Inspector and Prolific Novelist

If you think your morning commute is challenging, consider Anthony Trollope’s daily routine as a Post Office inspector in 1840s Ireland. Traveling by horseback through rural regions in all weather conditions, Trollope investigated postal irregularities, established new delivery routes, and negotiated with local officials—all while mentally crafting the complex social worlds that would fill his novels.

Trollope’s solution to balancing his demanding job with his literary ambitions was almost mechanical in its precision. Rising at 5:30 AM each morning, he positioned his watch before him and wrote for exactly three hours before heading to his postal duties. During these early sessions, he demanded 250 words from himself every quarter hour—a pace he maintained with remarkable consistency. If he finished a novel during a morning session, he would immediately begin another, never wasting a precious minute of his allocated writing time.

Trollope’s solution to balancing his demanding job with his literary ambitions was almost mechanical in its precision. Rising at 5:30 AM each morning, he positioned his watch before him and wrote for exactly three hours before heading to his postal duties. During these early sessions, he demanded 250 words from himself every quarter hour—a pace he maintained with remarkable consistency. If he finished a novel during a morning session, he would immediately begin another, never wasting a precious minute of his allocated writing time.

This disciplined approach yielded astonishing results. While maintaining his full-time Post Office career, Trollope produced 47 novels, numerous short stories, travel books, biographies, and even a classical translation. His literary output didn’t just survive alongside his day job—it thrived because of the structure it provided. “A small daily task, if it be really daily, will beat the labours of a spasmodic Hercules,” Trollope wrote in his autobiography, unwittingly creating a mantra for generations of writers juggling creative pursuits with professional obligations.

The Post Office didn’t just provide Trollope with a paycheck—it offered a wealth of material. His constant travel throughout Ireland and later England exposed him to people from every social class, from rural peasants to aristocrats, informing the rich social tapestry of novels like “The Warden” and “Barchester Towers.” His familiarity with bureaucracy, office politics, and the civil service system directly inspired works like “The Three Clerks,” which dissected government employment with an insider’s precision.

Perhaps most surprisingly, Trollope’s colleagues remained largely unaware of his flourishing second career for many years. When he finally achieved literary fame, some were reportedly shocked to discover their methodical postal inspector was also the creator of the beloved Barsetshire and Palliser novels that English readers devoured.

Trollope himself would later reject the romantic notion of writing as a pursuit requiring special circumstances or divine inspiration. In his autobiography, he famously declared, “All those I think who have lived as literary men—working daily as literary labourers—will agree with me that three hours a day will produce as much as a man ought to write.” It was a philosophy that transformed a civil servant into one of Victorian England’s most prolific and beloved novelists—all before most of his readers had even begun their workday.

Charlotte Brontë: Governess Who Created “Jane Eyre”

Charlotte Brontë knew intimately what it meant to be “a paid subordinate”—her own words from “Jane Eyre” that perfectly captured the precarious social position she occupied as a governess in Victorian England. Before becoming one of literature’s most beloved voices, Brontë spent years in the employment of wealthy families, enduring the peculiar limbo of being neither servant nor family member while responsible for educating children who often showed her little respect.

Between 1839 and 1845, Brontë moved between several governess positions and teaching posts, each one providing meager wages but rich material for her future masterpiece. The daily humiliations were numerous—being excluded from family gatherings yet expected to maintain perfect composure, having her intelligence questioned while simultaneously being tasked with cultivating young minds, and navigating unwanted attentions from male employers or their associates. These experiences would later fuel Jane Eyre’s fierce declarations of equality and dignity despite her station.

Between 1839 and 1845, Brontë moved between several governess positions and teaching posts, each one providing meager wages but rich material for her future masterpiece. The daily humiliations were numerous—being excluded from family gatherings yet expected to maintain perfect composure, having her intelligence questioned while simultaneously being tasked with cultivating young minds, and navigating unwanted attentions from male employers or their associates. These experiences would later fuel Jane Eyre’s fierce declarations of equality and dignity despite her station.

Finding time to write during these years required extraordinary determination. Unlike male authors who might retire to private studies, Brontë had precious few moments to herself. She snatched time in the evenings after her young charges were asleep, during rare free afternoons when the family was entertaining, or in early morning hours before the household stirred. Her writing desk was often a corner of the schoolroom where she taught during the day—the boundary between her paid work and creative life blurred by necessity.

When Brontë returned home to Haworth Parsonage between positions, her creative time remained fragmented. As the eldest surviving daughter, household management fell largely to her, with writing squeezed between domestic duties, caring for her ailing father, and supporting her sisters’ literary pursuits. The family’s dining room table served as their shared writing space, where the sisters would circle in the evenings, reading their work aloud to each other while simultaneously mending clothes or completing other necessary tasks.

The parallels between Brontë’s life and her heroine Jane’s are unmistakable. Jane’s plain-spoken challenges to authority, her insistence on being valued for her mind rather than appearance, and her navigation of complex power dynamics in employer relationships all reflect Brontë’s own struggles. The famous line, “I am a free human being with an independent will,” emerges not from abstract philosophizing but from years of practical experience in positions where such independence was actively discouraged.

When “Jane Eyre” was published in 1847 under the pseudonym Currer Bell, few readers could have imagined that its revolutionary voice—the “poor, obscure, plain, and little” governess who dared to claim equality with her employer—had been crafted in stolen moments by a woman who lived that very reality. Charlotte Brontë transformed the constraints and indignities of her working life into one of literature’s most enduring declarations of female autonomy, proving that sometimes the most confining circumstances can produce the most liberating art.

Wallace Stevens: Insurance Executive and Modernist Poet

In the mahogany-paneled executive offices of the Hartford Accident and Indemnity Company, Wallace Stevens commanded respect as a shrewd vice president and expert in surety law. His colleagues knew him as methodical, meticulous, and deeply knowledgeable about the insurance industry’s complexities. Few had any inkling that the same man was simultaneously revolutionizing American poetry with works of startling imagination and philosophical depth.

Stevens’ corporate ascent was as impressive as his poetic achievements. Joining Hartford in 1916 as an insurance lawyer, he rose steadily through the ranks, eventually becoming vice president in 1934—a position he maintained until his death in 1955. His business acumen was genuine; he specialized in complex surety bond claims and was considered an industry authority whose opinions carried significant weight in corporate decisions.

Stevens’ corporate ascent was as impressive as his poetic achievements. Joining Hartford in 1916 as an insurance lawyer, he rose steadily through the ranks, eventually becoming vice president in 1934—a position he maintained until his death in 1955. His business acumen was genuine; he specialized in complex surety bond claims and was considered an industry authority whose opinions carried significant weight in corporate decisions.

What makes Stevens’ double life particularly fascinating was his method of composition. During his daily two-mile walks between home and office, Stevens would compose poems in his head, working and reworking lines with each step. The rhythms of his walking became the rhythms of his verse. Upon arriving at work, he would dictate these compositions to his secretary, who would type them up—often without realizing she was transcribing groundbreaking modernist poetry rather than insurance correspondence.

Perhaps most curious was Stevens’ insistence on keeping his two identities almost completely separate. Many of his insurance colleagues remained unaware of his literary reputation even as he received major poetry awards. Conversely, his literary contemporaries often expressed surprise upon learning that the author of “The Emperor of Ice-Cream” and “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird” spent his days calculating risk assessments and negotiating claim settlements.

When asked about this compartmentalization, Stevens remarked, “It gives a man character as a poet to have this daily contact with a job.” Yet he rarely discussed poetry at the office or insurance in literary circles. This strict division wasn’t merely practical; it seemed essential to Stevens’ creative process—as if the tension between his structured business world and his imaginative poetic vision generated the necessary friction for his art.

The corporate environment that might have stifled another poet’s creativity instead provided Stevens with both financial security and a counterbalance to his abstract poetic explorations. His poems often grapple with the relationship between imagination and reality—a philosophical question he lived daily in his divided professional existence. In “The Idea of Order at Key West,” when Stevens writes of “the maker’s rage to order words of the sea,” one can almost glimpse the insurance executive imposing structure on the chaotic elements of language.

Stevens received the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1955, just months before his death. The award ceremony was attended by literary luminaries, but notably few from his insurance world. This final separation between his dual lives seems fitting for a poet who wrote, “The poem must resist the intelligence / Almost successfully”—even as he spent decades applying that same intelligence to the practical demands of corporate America.

Octavia Butler: From Factory Worker to Sci-Fi Legend

Long before Octavia Butler became the first science fiction writer to receive a MacArthur “Genius” Grant, she was waking before dawn to write stories after grueling shifts at jobs that had nothing to do with her literary ambitions. Butler’s journey to becoming one of the genre’s most revolutionary voices wasn’t paved with early recognition or privileged connections—it was built on countless pre-dawn writing sessions sandwiched between exhausting workdays.

Butler’s employment history reads like a catalog of thankless labor: potato chip factory worker, dishwasher, telemarketer, and warehouse clerk. She took these jobs not as temporary stepping stones but as necessary survival while pursuing her true passion. “I was working at all kinds of horrible little jobs because that’s what I could get,” Butler once recalled. “My mother had to quit school in the third grade to go to work, and she was determined I would get an education. But when I decided I was going to be a writer, she worried.”

Her writing schedule would have broken a less determined soul. Butler would rise at 2 AM, write until 5 AM, and then prepare for whatever job was paying her bills at the time. This wasn’t an occasional burst of productivity—it was her consistent practice for years. “Every day for years and years,” she noted in interviews, describing how she would fall asleep with her clothes laid out so she could maximize her precious writing time before work.

The rejection slips accumulated by the hundreds. From 1971, when she sold her first story, to 1976, when her first novel “Patternmaster” was published, Butler faced constant rejection. Yet she continued to write during those predawn hours, filling notebooks with stories about time travel, telepathy, and dystopian futures that explored profound questions about race, gender, and power. Her groundbreaking “Kindred”—now considered a cornerstone of both science fiction and African American literature—was written during this period of professional instability.

What kept Butler going through years of rejection wasn’t blind optimism but pragmatic determination. “You don’t start out writing good stuff,” she advised aspiring writers. “You start out writing crap and thinking it’s good stuff, and then gradually you get better at it. That’s why I say one of the most valuable traits is persistence.” That persistence was tested daily as she moved between exhausting jobs that left little mental energy for creative work.

Butler’s dual existence as laborer and writer directly informed her fiction. Her protagonists often navigate hostile environments with resilience and adaptability—qualities Butler herself demonstrated daily. The economic vulnerability experienced by many of her characters reflected her own precarious financial situation for much of her career. Even after achieving literary success, Butler maintained a practical approach to her writing career, living modestly and continuing to write with disciplined regularity.

When Butler finally broke through to wider recognition, becoming the first science fiction writer to receive a MacArthur Fellowship in 1995, it represented not just personal triumph but vindication for every early morning spent writing while the rest of the world slept. Her journey from factory floors to literary acclaim remains a powerful reminder that revolutionary art can emerge from the most seemingly ordinary circumstances—provided the artist possesses extraordinary persistence.

William Carlos Williams: Pediatrician Who Revolutionized American Poetry

For over four decades, parents in Rutherford, New Jersey, brought their children to the kindly doctor with the bow tie and gentle manner. Few realized that between checking throats and measuring fevers, Dr. William Carlos Williams was jotting down lines that would transform American poetry. The physician who delivered an estimated 3,000 babies during his career was simultaneously delivering some of modernism’s most influential poetic works—often written on prescription pads during brief moments between patients.

Williams maintained a grueling schedule that would exhaust most people. Rising early to make house calls, he’d see patients at his home office until late evening, sometimes attending births in the middle of the night. Unlike many of his literary contemporaries who fled to European artistic circles, Williams remained firmly rooted in small-town America, making his living treating the working-class families of Rutherford rather than pursuing academic positions or wealthy patrons.

Williams maintained a grueling schedule that would exhaust most people. Rising early to make house calls, he’d see patients at his home office until late evening, sometimes attending births in the middle of the night. Unlike many of his literary contemporaries who fled to European artistic circles, Williams remained firmly rooted in small-town America, making his living treating the working-class families of Rutherford rather than pursuing academic positions or wealthy patrons.

His writing method was necessarily opportunistic. “I would be interrupted, called away to deliver a baby or whatever, and would return to my desk to find the fragment lying there to be continued,” Williams recalled. These fragments—often composed on prescription pads, envelopes, or whatever paper was at hand—would eventually coalesce into poems like “The Red Wheelbarrow” and “This Is Just To Say,” works whose seemingly simple language masked profound innovations in poetic form.

What makes Williams particularly fascinating among working writers was his insistence that his medical practice enriched rather than detracted from his art. “My ‘medicine’ was the thing that gained me entrance to these secret gardens of the self,” he wrote. “It lay there, another world, in the self.” His daily interactions with patients across all social classes gave him intimate access to American life in all its raw, unvarnished reality—experiences that directly shaped his literary vision.

This connection between medicine and poetry wasn’t merely philosophical for Williams. His poems often draw directly from medical observations, finding extraordinary meaning in ordinary moments of human vulnerability. His training in scientific observation gave his writing a precision and clarity that became hallmarks of his style. As he famously wrote: “No ideas but in things”—a creative philosophy that merged his physician’s empiricism with his poet’s sensibility.

While contemporaries like T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound built their literary careers in academic and publishing circles, Williams stubbornly maintained his medical practice, believing it kept him connected to the authentic American experience he sought to capture in his work. This choice wasn’t without cost—recognition came slower for Williams than for his expatriate peers. His groundbreaking collection “Spring and All” was initially published in an edition of just 300 copies, and widespread acclaim didn’t arrive until late in his career.

When Williams suffered a series of strokes in his later years that limited his medical practice, he reflected that his dual career had given him a completeness few artists experience: “As a writer, I have never felt that medicine interfered with me but rather that it was my very food and drink, the very thing which made it possible for me to write.” In his life and work, Williams proved that great art doesn’t require removal from ordinary life—sometimes it thrives precisely because of deep immersion in the everyday world of work and service.

Conclusion

So what’s the real takeaway from these literary giants who balanced spreadsheets and stethoscopes with sonnets and stories? First off, you’re definitely not alone in that constant hustle between creative passion and paying the bills. These authors weren’t succeeding despite their day jobs—they were often succeeding because of them.

Notice the patterns here? None of these writers waited for the “perfect conditions” to create. Instead, they built ruthlessly efficient routines that worked within the constraints of busy lives. Trollope demanded exactly 250 words from himself every fifteen minutes before heading to his postal duties. Morrison woke at 4 AM because those precious pre-dawn hours were the only ones truly hers. Stevens transformed his daily commute into a mobile writing studio, composing poems with each step between home and office.

What’s particularly fascinating is how their “ordinary” work lives infiltrated and enriched their writing in ways that might never have happened in a full-time literary bubble. Kafka’s nightmarish bureaucracies sprang directly from his insurance office experiences. Williams found poetry in his patients’ vulnerable moments. Brontë channeled the complex power dynamics she navigated as a governess into Jane Eyre’s revolutionary voice. Their day jobs weren’t just paying the bills—they were providing irreplaceable material.

So the next time you’re squeezing in writing sessions between Zoom meetings or editing your manuscript during your lunch break, remember: you’re not just making do with less-than-ideal circumstances. You’re actually following the exact path that produced some of literature’s most groundbreaking works. That spreadsheet you’re managing or classroom you’re teaching isn’t keeping you from your real work—it might be quietly informing it in ways you don’t yet recognize.

The great paradox these writers reveal is that constraints often fuel creativity rather than hinder it. Limited time forces efficiency. Diverse experiences provide unique perspectives. And perhaps most importantly, staying connected to the working world keeps writing grounded in authentic human experience.

Your masterpiece might be taking shape right now in the margins of a busy life. And someday, future writers might draw inspiration from how you managed to change literature forever—one lunch break at a time.

- Story Structure: How the Save the Cat! Method Can Transform Your Writing - April 23, 2025

- HALFWAY TO HALLOWEEN: 50 Words of Horror Contest - April 22, 2025

- How to Edit your poetry for beginners and beyond (with worksheet) - April 18, 2025