Introduction to Oscar Wilde’s Review of “A Manual of Oil Painting” A.K.A Common Sense in Art.

This page was updated March 28, 2025.

In this delightfully sardonic 1887 review from the Pall Mall Gazette, Oscar Wilde takes aim at John Collier’s decidedly pedestrian approach to art instruction. With his characteristic wit and irony, Wilde dissects Collier’s “Manual of Oil Painting,” a book that reduces the sublime act of artistic creation to a set of mechanical procedures and common-sense rules.

Wilde’s review brilliantly illustrates his belief that art transcends mere technical reproduction—a philosophy that would later find full expression in works like “The Decay of Lying” and “The Picture of Dorian Gray.” Through carefully crafted satire, Wilde reveals his disdain for those who would strip art of its mystery, imagination, and spiritual qualities.

The review offers modern readers a glimpse into the aesthetic debates of Victorian England and showcases Wilde at his critical best: elegant, incisive, and deliciously subversive. As you read this piece, notice how Wilde appears to praise Collier’s “sturdy” and “downright” approach while simultaneously undermining it with subtle mockery—a masterclass in the art of critical irony.

At this critical moment in the artistic development of England Mr. John Collier has come forward as the champion of common-sense in art. It will be remembered that Mr. Quilter, in one of his most vivid and picturesque metaphors, compared Mr. Collier’s method as a painter to that of a shampooer in a Turkish bath. {119} As a writer Mr. Collier is no less interesting. It is true that he is not eloquent, but then he censures with just severity ‘the meaningless eloquence of the writers on æsthetics’; we admit that he is not subtle, but then he is careful to remind us that Leonardo da Vinci’s views on painting are nonsensical; his qualities are of a solid, indeed we may say of a stolid order; he is thoroughly honest, sturdy and downright, and he advises us, if we want to know anything about art, to study the works of ‘Helmholtz, Stokes, or Tyndall,’ to which we hope we may be allowed to add Mr. Collier’s own Manual of Oil Painting.

For this art of painting is a very simple thing indeed, according to Mr. Collier. It consists merely in the ‘representation of natural objects by means of pigments on a flat surface.’ There is nothing, he tells us, ‘so very mysterious’ in it after all. ‘Every natural object appears to us as a sort of pattern of different shades and colours,’ and ‘the task of the artist is so to arrange his shades and colours on his canvas that a similar pattern is produced.’ This is obviously pure common-sense, and it is clear that art-definitions of this character can be comprehended by the very meanest capacity and, indeed, may be said to appeal to it. For the perfect development, however, of this pattern-producing faculty a severe training is necessary. The art student must begin by painting china, crockery, and ‘still life’ generally. He should rule his straight lines and employ actual measurements wherever it is possible. He will also find that a plumb-line comes in very useful. Then he should proceed to Greek sculpture, for from pottery to Phidias is only one step. Ultimately he will arrive at the living model, and as soon as he can ‘faithfully represent any object that he has before him’ he is a painter. After this there is, of course, only one thing to be considered, the important question of subject. Subjects, Mr. Collier tells us, are of two kinds, ancient and modern. Modern subjects are more healthy than ancient subjects, but the real difficulty of modernity in art is that the artist passes his life with respectable people, and that respectable people are unpictorial. ‘For picturesqueness,’ consequently, he should go to ‘the rural poor,’ and for pathos to the London slums. Ancient subjects offer the artist a very much wider field. If he is fond of ‘rich stuffs and costly accessories’ he should study the Middle Ages; if he wishes to paint beautiful people, ‘untrammelled by any considerations of historical accuracy,’ he should turn to the Greek and Roman mythology; and if he is a ‘mediocre painter,’ he should choose his ‘subject from the Old and New Testament,’ a recommendation, by the way, that many of our Royal Academicians seem already to have carried out. To paint a real historical picture one requires the assistance of a theatrical costumier and a photographer. From the former one hires the dresses and the latter supplies one with the true background. Besides subject-pictures there are also portraits and landscapes. Portrait painting, Mr. Collier tells us, ‘makes no demands on the imagination.’ As is the sitter, so is the work of art. If the sitter be commonplace, for instance, it would be ‘contrary to the fundamental principles of portraiture to make the picture other than commonplace.’ There are, however, certain rules that should be followed. One of the most important of these is that the artist should always consult his sitter’s relations before he begins the picture. If they want a profile he must do them a profile; if they require a full face he must give them a full face; and he should be careful also to get their opinion as to the costume the sitter should wear and ‘the sort of expression he should put on.’ ‘After all,’ says Mr. Collier pathetically, ‘it is they who have to live with the picture.’

Besides the difficulty of pleasing the victim’s family, however, there is the difficulty of pleasing the victim. According to Mr. Collier, and he is, of course, a high authority on the matter, portrait painters bore their sitters very much. The true artist consequently should encourage his sitter to converse, or get some one to read to him; for if the sitter is bored the portrait will look sad. Still, if the sitter has not got an amiable expression naturally the artist is not bound to give him one, nor ‘if he is essentially ungraceful’ should the artist ever ‘put him in a graceful attitude.’ As regards landscape painting, Mr. Collier tells us that ‘a great deal of nonsense has been talked about the impossibility of reproducing nature,’ but that there is nothing really to prevent a picture giving to the eye exactly the same impression that an actual scene gives, for that when he visited ‘the celebrated panorama of the Siege of Paris’ he could hardly distinguish the painted from the real cannons! The whole passage is extremely interesting, and is really one out of many examples we might give of the swift and simple manner in which the common-sense method solves the great problems of art. The book concludes with a detailed exposition of the undulatory theory of light according to the most ancient scientific discoveries. Mr. Collier points out how important it is for an artist to hold sound views on the subject of ether waves, and his own thorough appreciation of Science may be estimated by the definition he gives of it as being ‘neither more nor less than knowledge.’

Mr. Collier has done his work with much industry and earnestness. Indeed, nothing but the most conscientious seriousness, combined with real labour, could have produced such a book, and the exact value of common-sense in art has never before been so clearly demonstrated.

A Manual of Oil Painting. By the Hon. John Collier. (Cassell and Co.)

First appeared in Pall Mall Gazette, January 8, 1887.

Why This Review Matters: Wilde’s Defense of Artistic Vision

This seemingly modest review holds significant importance beyond its immediate critique of Collier’s manual. First, it represents a critical moment in the aesthetic debates of the late Victorian era, when competing philosophies about the purpose and practice of art were vigorously contested. Wilde’s position against Collier’s mechanical approach to painting exemplifies the broader tension between technical craftsmanship and artistic imagination that continues to resonate in artistic discourse today.

The review also serves as an early articulation of Wilde’s developing aesthetic philosophy. Written several years before his more famous critical essays, we can observe Wilde’s emerging conviction that art should transcend mere imitation of nature—a principle that would become central to his aesthetic theory. His mockery of Collier’s suggestion that art is simply “the representation of natural objects by means of pigments on a flat surface” foreshadows his later, more explicit rejection of mimesis in favor of art that prioritizes beauty and imagination.

Furthermore, this piece illuminates Wilde’s brilliant critical method. His technique of using apparent praise to deliver devastating criticism demonstrates his mastery of irony as a critical tool. Rather than directly attacking Collier, Wilde seemingly celebrates the author’s “common-sense” while systematically revealing how such an approach strips art of its essential magic and meaning.

For scholars and enthusiasts of Wilde’s work, this review provides valuable context for understanding his intellectual development and the consistency of his aesthetic values throughout his career. It also offers insight into the artistic environment of late nineteenth-century England, highlighting the institutional tensions between traditional academic approaches to art (represented by Collier) and the more revolutionary artistic movements that Wilde championed.

Finally, the review remains remarkably relevant to contemporary discussions about art education and practice, reminding us that the debate between technical instruction and creative inspiration continues to shape how we understand and teach artistic disciplines in the modern era.

Analysis of Oscar Wilde’s Review of “A Manual of Oil Painting”

In this brilliantly sardonic review, Oscar Wilde employs sustained irony to dismantle John Collier’s reductive approach to art instruction. By seemingly praising Collier as “the champion of common-sense in art” while methodically revealing the absurdity of his mechanical methods, Wilde creates a devastating critique without direct antagonism. His careful selection and framing of Collier’s own words—such as defining painting merely as “the representation of natural objects by means of pigments on a flat surface”—allows the text’s limitations to expose themselves.

The review represents a fundamental clash between competing artistic philosophies in late Victorian England. While Collier advocates a purely technical, imitative approach to art that can be systematically taught, Wilde subtly argues for art that transcends mere reproduction and embraces imagination and beauty. This philosophical tension appears throughout the piece, particularly when Wilde mockingly recounts Collier’s pride in not being able to distinguish between real and painted cannons in a panorama—questioning whether art’s highest achievement is simply to trick the eye.

Beyond its aesthetic debate, the review offers social commentary through its treatment of Collier’s practical advice. Wilde’s sardonic presentation of recommendations for portrait painters to consult the sitter’s family about pose and expression because “it is they who have to live with the picture” reveals the commercial constraints on Victorian artists. Similarly, the suggestion that artists should seek “picturesqueness” from “the rural poor” and “pathos” from London slums exposes the class dynamics underlying artistic production of the era. Through this compact but multilayered critique, Wilde not only dismisses a specific text but articulates his developing vision of art that would later find fuller expression in his major aesthetic writings.

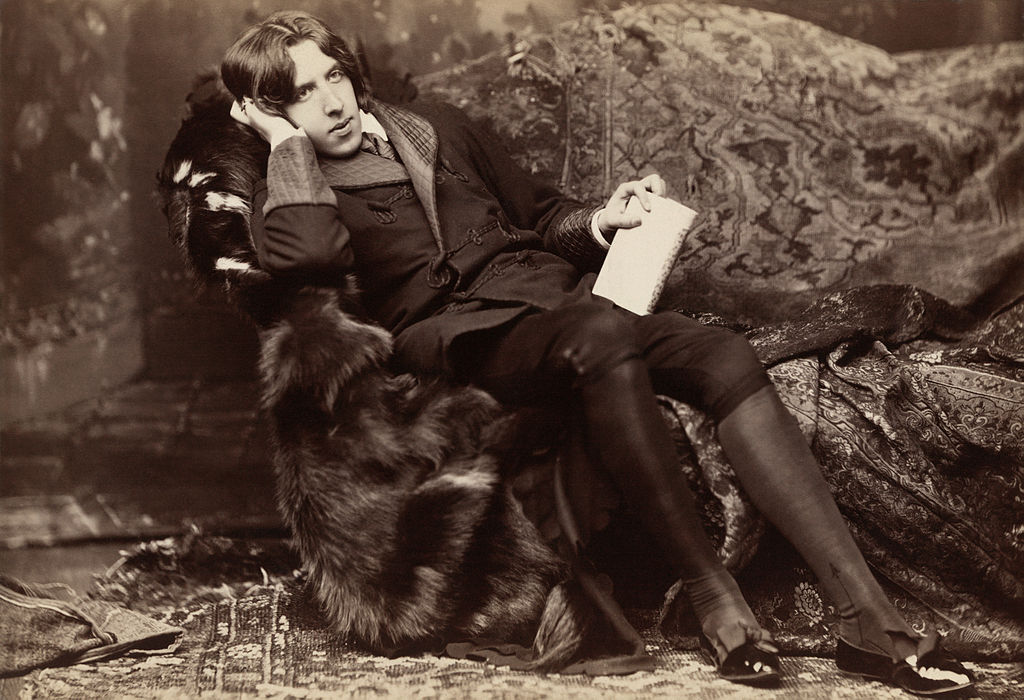

Oscar Wilde: A Brief Biography

Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) was an Irish poet, playwright, novelist, and wit who became one of the most celebrated literary figures of the late Victorian era. After distinguished academic careers at Trinity College Dublin and Oxford University, he established himself in London society as a master of conversation and aestheticism. Wilde achieved his greatest success with society comedies like “The Importance of Being Earnest” (1895), while his novel “The Picture of Dorian Gray” (1890) and critical essays articulated his “art for art’s sake” philosophy.

His career was destroyed in 1895 when he was convicted of “gross indecency” for homosexual acts and sentenced to two years of hard labor. After his release, the broken writer lived in exile in France under the name Sebastian Melmoth until his death at age 46. Despite his tragically shortened career, Wilde’s literary brilliance, epigrammatic wit, and personal courage have established him as an enduring cultural icon and an early symbol of artistic and sexual freedom.

Further Reading

For those interested in exploring Oscar Wilde’s art criticism further, several works provide valuable context:

Primary Sources:

- “The Critic as Artist” and “The Decay of Lying” in Wilde’s collection Intentions (1891) elaborate on the aesthetic theories hinted at in this review

- Wilde’s other art reviews for the Pall Mall Gazette offer similar insights into his aesthetic judgments

- “The Soul of Man Under Socialism” touches on Wilde’s views about art’s purpose in society

Secondary Sources:

- Lawrence Danson’s Wilde’s Intentions: The Artist in His Criticism provides scholarly analysis of Wilde’s critical works

- Nicholas Frankel’s Oscar Wilde: The Unrepentant Years explores Wilde’s aesthetic philosophy

- Elizabeth Prettejohn’s Art for Art’s Sake: Aestheticism in Victorian Painting examines the broader artistic context of Wilde’s criticism

For similar art criticism from the period, readers might enjoy John Ruskin’s writings on art and society, Walter Pater’s Studies in the History of the Renaissance (which greatly influenced Wilde), and Matthew Arnold’s cultural criticism, all of which engage with questions about art’s purpose and ideal forms during this pivotal period in aesthetic thought.

- How to Edit your poetry for beginners and beyond (with worksheet) - April 18, 2025

- 20 Forgotten Gothic Stories Writers Need to Rediscover - April 18, 2025

- The Writer’s Roadmap: Embracing Outlining (Free Worksheet Included!) - April 15, 2025