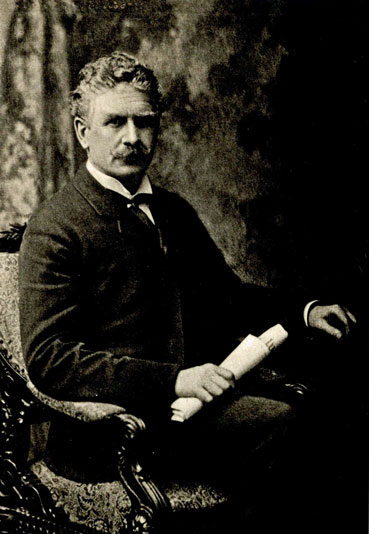

A Look at Aims and the Plans

by Ambrose Bierce

In 1909 Ambrose Bierce famous for many of his works including An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge wrote a piece of advice to writers titled “Write it Right.” The piece starts with some words of wisdom to the writer and then is followed by a long “Black List of Literary Faults.” We thought with the language changing, the internet, text messaging it might be interesting to take a look at some of the items on Ambrose’s list. Needless to say it does not seem he would have been amused by lol, or ttyl. Much of the list is still solid, but the way Bierce can be taken is a little stern. Some of these are pretty funny. The advice is first and then we’ve included only sum of the list, there are many more.

The author’s main purpose in this book is to teach precision in writing; and of good writing (which, essentially, is clear thinking made visible) precision is the point of capital concern. It is attained by choice of the word that accurately and adequately expresses what the writer has in mind, and by exclusion of that which either denotes or connotes something else. As Quintilian puts it, the writer should so write that his reader not only may, but must, understand.

Few words have more than one literal and serviceable meaning, however many metaphorical, derivative, related, or even unrelated, meanings lexicographers may think it worth while to gather from all sorts and conditions of men, with which to bloat their absurd and misleading dictionaries. This actual and serviceable meaning—not always determined by derivation, and seldom by popular usage—is the one affirmed, according to his light, by the author of this little manual of solecisms. Narrow etymons of the mere scholar and loose locutions of the ignorant are alike denied a standing.

The plan of the book is more illustrative than expository, the aim being to use the terms of etymology and syntax as little as is compatible with clarity, familiar example being more easily apprehended than technical precept. When both are employed the precept is commonly given after the example has prepared the student to apply it, not only to the matter in mind, but to similar matters not mentioned. Everything in quotation marks is to be understood as disapproved.

Not all locutions blacklisted herein are always to be reprobated as universal outlaws. Excepting in the case of capital offenders—expressions ancestrally vulgar or irreclaimably degenerate—absolute proscription is possible as to serious composition only; in other forms the writer must rely on his sense of values and the fitness of things. While it is true that some colloquialisms and, with less of license, even some slang, may be sparingly employed in light literature, for point, piquancy or any of the purposes of the skilled writer sensible to the necessity and charm of keeping at least one foot on the ground, to others the virtue of restraint may be commended as distinctly superior to the joy of indulgence.

Precision is much, but not all; some words and phrases are disallowed on the ground of taste. As there are neither standards nor arbiters of taste, the book can do little more than reflect that of its author, who is far indeed from professing impeccability. In neither taste nor precision is any man’s practice a court of last appeal, for writers all, both great and small, are habitual sinners against the light; and their accuser is cheerfully aware that his own work will supply (as in making this book it has supplied) many “awful examples”—his later work less abundantly, he hopes, than his earlier. He nevertheless believes that this does not disqualify him for showing by other instances than his own how not to write. The infallible teacher is still in the forest primeval, throwing seeds to the white blackbirds.

A.B.

The Blacklist

Admission for Admittance. “The price of admission is one dollar.”

Adopt. “He adopted a disguise.” One may adopt a child, or an opinion, but a disguise is assumed.

All of. “He gave all of his property.” The words are contradictory: an entire thing cannot be of itself. Omit the preposition.

Allow for Permit. “I allow you to go.” Precision is better attained by saying permit, for allow has other meanings.

Approve of for Approve. There is no sense in making approve an intransitive verb.

Authoress. A needless word—as needless as “poetess.”

Bogus for Counterfeit, or False. The word is slang; keep it out.

Brainy. Pure slang, and singularly disagreeable.

Bug for Beetle, or for anything. Do not use it.

Cannot for Can. “I cannot but go.” Say, I can but go.

Casket for Coffin. A needless euphemism affected by undertakers.

Casualties for Losses in Battle. The essence of casualty is accident, absence of design. Death and wounds in battle are produced otherwise, are expectable and expected, and, by the enemy, intentional.

Climb down. In climbing one ascends

Commit Suicide. Instead of “He committed suicide,” say, He killed himself, or, He took his life. For married we do not say “committed matrimony.” Unfortunately most of us do say, “got married,” which is almost as bad. For lack of a suitable verb we just sometimes say committed this or that, as in the instance of bigamy, for the verb to bigam is a blessing that is still in store for us.

Demise for Death. Usually said of a person of note. Demise means the lapse, as by death, of some authority, distinction or privilege, which passes to another than the one that held it; as the demise of the Crown.

Dépôt for Station. “Railroad dépôt.” A dépôt is a place of deposit; as, a dépôt of supply for an army.

Doubtlessly. A doubly adverbial form, like “illy.”

Electrocution. To one having even an elementary knowledge of Latin grammar this word is no less than disgusting, and the thing meant by it is felt to be altogether too good for the word’s inventor.

Extend for Proffer. “He extended an invitation.” One does not always hold out an invitation in one’s hand; it may be spoken or sent.

Financial for Pecuniary. “His financial reward”; “he is financially responsible,” and so forth.

Fix. This is, in America, a word-of-all-work, most frequently meaning repair, or prepare. Do not so use it.

Funds for Money. “He was out of funds.” Funds are not money in general, but sums of money or credit available for particular purposes.

Gent for Gentleman. Vulgar exceedingly.

Given. “The soldier was given a rifle.” What was given is the rifle, not the soldier. “The house was given a coat (coating) of paint.” Nothing can be “given” anything.

Goatee. In this country goatee is frequently used for a tuft of beard on the point of the chin—what is sometimes called “an imperial,” apparently because the late Emperor Napoleon III wore his beard so. His Majesty the Goat is graciously pleased to wear his beneath the chin.

Got Married for Married. If this is correct we should say, also, “got dead” for died; one expression is as good as the other.

Grueling. Used chiefly by newspaper reporters; as, “He was subjected to a grueling cross-examination.” “It was grueling weather.” Probably a corruption of grilling.

Head over Heels. A transposition of words hardly less surprising than (to the person most concerned) the mischance that it fails to describe. What is meant is heels over head.

Honeymoon. Moon here means month, so it is incorrect to say, “a week’s honeymoon,” or, “Their honeymoon lasted a year.”

Identified with. “He is closely identified with the temperance movement.” Say, connected.

Indorse. See Endorse.

Insane Asylum. Obviously an asylum cannot be unsound in mind. Say, asylum for the insane.

Jackies for Sailors. Vulgar, and especially offensive to seamen.

Later on. On is redundant; say, later.

Laundry. Meaning a place where clothing is washed, this word cannot mean, also, clothing sent there to be washed.

Lay (to place) for Lie (to recline). “The ship lays on her side.” A more common error is made in the past tense, as, “He laid down on the grass.” The confusion comes of the identity of a present tense of the transitive verb to lay and the past tense of the intransitive verb to lie.

Mad for Angry. An Americanism of lessening prevalence. It is probable that anger is a kind of madness (insanity), but that is not what the misusers of the word mad mean to affirm.

New Beginner for Beginner.

Numerous for Many. Rightly used, numerous relates to numbers, but does not imply a great number. A correct use is seen in the term numerous verse—verse consisting of poetic numbers; that is, rhythmical feet.

Obnoxious for Offensive. Obnoxious means exposed to evil. A soldier in battle is obnoxious to danger.

Occasion for Induce, or Cause. “His arrival occasioned a great tumult.” As a verb, the word is needless and unpleasing.

Occasional Poems. These are not, as so many authors and compilers seem to think, poems written at irregular and indefinite intervals, but poems written for occasions, such as anniversaries, festivals, celebrations and the like.

Pay. “Laziness does not pay.” “It does not pay to be uncivil.” This use of the word is grossly commercial. Say, Indolence is unprofitable. There is no advantage in incivility.

Restive for Restless. These words have directly contrary meanings; the dictionaries’ disallowance of their identity would be something to be thankful for, but that is a dream.

Retire for Go to Bed. English of the “genteel” sort. See Genteel.

Some for Somewhat. “He was hurt some.”

Soon for Willingly. “I would as soon go as stay.” “That soldier would sooner eat than fight.” Say, rather eat.

Tantamount for Equivalent. “Apology is tantamount to confession.” Let this ugly word alone; it is not only illegitimate, but ludicrously suggests catamount.

Tasty for Tasteful. Vulgar.

Ugly for Ill-natured, Quarrelsome. What is ugly is the temper, or disposition, not the person having it.

Under-handed and Under-handedly for Under-hand. See Off-handed.

Unique. “This is very unique.” “The most unique house in the city.” There are no degrees of uniqueness: a thing is unique if there is not another like it. The word has nothing to do with oddity, strangeness, nor picturesqueness.

Vulgar for Immodest, Indecent. It is from vulgus, the common people, the mob, and means both common and unrefined, but has no relation to indecency.

Way for Away. “Way out at sea.” “Way down South.”

Win for Won. “I went to the race and win ten dollars.” This atrocious solecism seems to be unknown outside the world of sport, where may it ever remain.

Without for Unless. “I cannot go without I recover.” Peasantese.

- Story Structure: How the Save the Cat! Method Can Transform Your Writing - April 23, 2025

- HALFWAY TO HALLOWEEN: 50 Words of Horror Contest - April 22, 2025

- How to Edit your poetry for beginners and beyond (with worksheet) - April 18, 2025