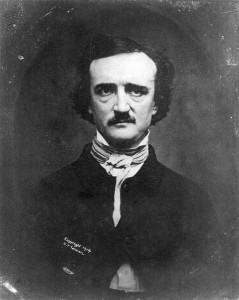

(One Poe’s Birthday!)

One does not feel, by any means, that the last word has been uttered upon this great artist. Has attention been called, for instance, to the sardonic cynicism which underlies his most thrilling effects? Poe’s cynicism is itself a very fascinating pathological subject. It is an elaborate thing, compounded of many strange elements. There is a certain dark, wilful melancholy in it that turns with loathing from all human comfort. There is also contempt in it, and savage derision. There is also in it a quality of mood that I prefer to call Saturnian—the mood of those born under the planet Saturn. There is cruelty in it, too, and voluptuous cruelty, though cold, reserved, and evasive. It is this “cynicism” of his which makes it possible for him to introduce into his poetry—it is of his poetry that I wish to speak—a certain colloquial salt, pungent and acrid, and with the smell of the tomb about it. It is colloquialism; but it is such colloquialism as ghosts or vampires would use.

One does not feel, by any means, that the last word has been uttered upon this great artist. Has attention been called, for instance, to the sardonic cynicism which underlies his most thrilling effects? Poe’s cynicism is itself a very fascinating pathological subject. It is an elaborate thing, compounded of many strange elements. There is a certain dark, wilful melancholy in it that turns with loathing from all human comfort. There is also contempt in it, and savage derision. There is also in it a quality of mood that I prefer to call Saturnian—the mood of those born under the planet Saturn. There is cruelty in it, too, and voluptuous cruelty, though cold, reserved, and evasive. It is this “cynicism” of his which makes it possible for him to introduce into his poetry—it is of his poetry that I wish to speak—a certain colloquial salt, pungent and acrid, and with the smell of the tomb about it. It is colloquialism; but it is such colloquialism as ghosts or vampires would use.

Poe remains—that has been already said, has it not?—absolutely cold while he produces his effects. There is a frozen contempt indicated in every line he writes for the poor facile artists “who speak with tears.” Yet the moods through which his Annabels and Ligeias and Ulalumes lead us are moods he must surely himself have known. Yes, he knew them; but they were, so to speak, so completely the atmosphere he lived in that there was no need for him to be carried out of himself when he wrote of them; no need for anything but icy, pitiless transcription. Has it been noticed how inhumanly immoral this great poet is? Not because he drank wine or took drugs. All that has been exaggerated, and, anyway, what does it matter now? But in a much deeper and more deadly sense. It is strange! The world makes such odd blunders. It seems possessed of the idea that absurd amorous scamps like Casanova reach the bottom of wickedness. They do not even approach it. Intrinsically they are quite stupidly “good.” Then, again, Byron is supposed to have been a wicked man. He himself aspired to be nothing less. But he was everything less. He was a great, greedy, selfish, swaggering, magnanimous infant! Oscar Wilde is generally regarded as something short of “the just man made perfect,” but his simple, babyish passion for touching pretty things, toying with pretty people, wearing pretty clothes, and drinking absinthe, is far too naive a thing to be, at bottom, evil. No really wicked person could have written “The Importance of Being Earnest,” with those delicious, paradoxical children rallying one another, and “Aunt Augusta” calling aloud for cucumber-sandwiches! Salome itself—that Scarlet Litany—which brings to us, as in a box of alabaster, all the perfumes and odours of amorous lust, is not really a “wicked” play; not wicked, that is to say, unless all mad passion is wicked. Certainly the lust in “Salome” smoulders and glows with a sort of under-furnace of concentration, but, after all, it is the old, universal obsession. Why is it more wicked to say, “Suffer me to kiss thy mouth, Jokanaan!” than to say, “Her lips suck forth my soul—see where it flies!”? Why is it more wicked to say, “Thine eyes are like black holes, burnt by torches in Tyrian tapestry!” than to cry out, as Antony cries out, for the hot kisses of Egypt? Obviously the madness of physical desire is a thing that can hardly be tempered down to the quiet stanzas of Gray’s Elegy. But it is not in itself a wicked thing; or the world would never have consecrated it in the great Love-Legends. One may admit that the entrance of the Nubian Executioner changes the situation; but, after all, the frenzy of the girl’s request—the terror of that Head upon the silver charger—were implicit in her passion from the beginning; and are, God knows! never very far from passion of that kind.

But all this is changed when we come to Edgar Allen Poe. Here we are no longer in Troy or Antioch or Canopus or Rimini. Here it is not any more a question of ungovernable passion carried to the limit of madness. Here it is no more the human, too human, tradition of each man “killing” the “thing he loves.” Here we are in a world where the human element, in passion, has altogether departed, and left something else in its place; something which is really, in the true sense, “inhumanly immoral.” In the first place, it is a thing devoid of any physical emotion. It is sterile, immaterial, unearthly, ice-cold. In the second place, it is, in a ghastly sense, self-centered! It feeds upon itself. It subdues everything to itself. Finally, let it be said, it is a thing with a mania for Corruption. The Charnel-House is its bridal-couch, and the midnight stars whisper to one another of its perversion. There is no need for it “to kill the thing it loves,” for it loves only what is already dead. Favete linguis! There must be no profane misinterpretation of this subtle and delicate difference. In analysing the evasive chemistry of a great poet’s mood, one moves warily, reverently, among a thousand betrayals. The mind of such a being is as the sand-strewn floor of a deep sea. In this sea we poor divers for pearls, and stranger things, must hold our breath long and long, as we watch the great glittering fish go sailing by, and touch the trailing, rose-coloured weeds, and cross the buried coral. It may be that no one will believe us, when we return, about what we have seen! About those carcanets of rubies round drowned throats and those opals that shimmered and gleamed in dead men’s skulls!

At any rate, the most superficial critic of Poe’s poetry must admit that every single one of his great verses, except the little one “to Helen,” is pre-occupied with Death. Even in that Helen one, perhaps the loveliest, though, I do not think, the most characteristic, of all, the poet’s desire is to make of the girl he celebrates a sort of Classic Odalisque, round whose palpable contours and lines he may hang the solemn ornaments of the Dead—of the Dead to whom his soul turns, even while embracing the living! Far, far off, from where the real Helen waits, so “statue-like”—the “agate lamp” in her hands—wavers the face of that other Helen, the face “that launched a thousand ships, and burnt the topless towers of Ilium.”

The longer poem under the same title, and apparently addressed to the same sorceress, is more entirely “in his mood.” Those shadowy, moon-lit “parterres,” those living roses—Beardsley has planted them since in another “enchanted garden”—and those “eyes,” that grow so luminously, so impossibly large, until it is almost pain to be “saved” by them—these things are in Poe’s true manner; for it is not “Helen” that he has ever loved, but her body, her corpse, her ghost, her memory, her sepulchre, her look of dead reproach! And these things none can take from him. The maniacal egoism of a love of this kind—its frozen inhumanity—can be seen even in those poems which stretch yearning hands towards Heaven. In “Annabel Lee,” for instance, in that sea-kingdom where the maiden lived who had no thought—who must have no thought—”but to love and be loved by me”—what madness of implacable possession, in that “so all the night-tide I lie down by the side of my darling, my darling, my life and my bride, in her sepulchre there by the sea, in her tomb by the sounding sea!”

The same remorseless “laying on of hands” upon what God himself cannot save from us may be discerned in that exquisite little poem which begins:

“Thou wast all to me, love,

For which my soul did pine;

A green isle in the Sea, love,

A Fountain and a Shrine

All wreathed with Fairy fruits and flowers;

And all the flowers were mine!”

That “dim-gulf” o’er which “the spirit lies, mute, motionless, aghast”—how well, in Poe’s world, we know that! For still, in those days of his which are “trances,” and in those “nightly dreams” which are all he lives for, he is with her; with her still, with her always;

“In what ethereal dances,

By what eternal streams!”

The essence of “immorality” does not lie in mad Byronic passion, or in terrible Herodian lust. It lies in a certain deliberate “petrifaction” of the human soul in us; a certain glacial detachment from all interests save one; a certain frigid insanity of preoccupation with our own emotion. And this emotion, for the sake of which every earthly feeling turns to ice, is our Death-hunger, our eternal craving to make what has been be again, and again, forever!

The essence of “immorality” does not lie in mad Byronic passion, or in terrible Herodian lust. It lies in a certain deliberate “petrifaction” of the human soul in us; a certain glacial detachment from all interests save one; a certain frigid insanity of preoccupation with our own emotion. And this emotion, for the sake of which every earthly feeling turns to ice, is our Death-hunger, our eternal craving to make what has been be again, and again, forever!

The essence of immorality lies not in the hot flame of natural, or even unnatural, desire. It lies in that inhuman and forbidden wish to arrest the processes of life—to lay a freezing hand—a dead hand—upon what we love, so that it shall always be the same. The really immoral thing is to isolate, from among the affections and passions and attractions of this human world, one particular lure; and then, having endowed this with the living body of “eternal death,” to bend before it, like the satyr before the dead nymph in Aubrey’s drawing, and murmur and mutter and shudder over it, through the eternal recurrence of all things!

Is it any longer concealed from us wherein the “immorality” of this lies? It lies in the fact that what we worship, what we will not, through eternity, let go, is not a living person, but the “body” of a person; a person who has so far been “drugged,” as not only to die for us—that is nothing!—but to remain dead for us, through all the years!

In his own life—with that lovely consumptive Child-bride dying by his side—Edgar Allen Poe lived as “morally,” as rigidly, as any Monk. The popular talk about his being a “Drug-Fiend” is ridiculous nonsense. He was a laborious artist, chiselling and refining his “artificial” poems, day in and day out. Where his “immorality” lies is much deeper. It is in the mind—the mind, Master Shallow!—for he is nothing if not an absolute “Cerebralist.” Certainly Poe’s verses are “artificial.” They are the most artificial of all poems ever written. And this is natural, because they were the premeditated expression of a premeditated cult. But to say they are artificial does not derogate from their genius. Would that there were more such “artificial” verses in the world!

One wonders if it is clearly understood how the “unearthly” element in Poe differs from the “unearthly” element in Shelley. It differs from it precisely as Death differs from Life.

Shelley’s ethereal spiritualism—though, God knows, such gross animals are we, it seems inhuman enough—is a passionate white flame. It is the thin, wavering fire-point of all our struggles after purity and eternity. It is a centrifugal emotion, not, as was the other’s, a centripedal one. It is the noble Platonic rising from the love of one beautiful person to the love of many beautiful persons; and from that onward, through translunar gradations, to the love of the supreme Beauty itself. Shelley’s “spirituality” is a living, growing, creative thing. In its intrinsic nature it is not egoistic at all, but profoundly altruistic. It uses Sex to leave Sex behind. In its higher levels it is absolutely Sexless. It may transcend humanity, but it springs from humanity. It is, in fact, humanity’s dream of its own transmutation. For all its ethereality and remoteness, it yearns, “like a God in pain,” over the sorrows of the world. With infinite planetary pity, it would heal those sorrows.

Edgar Allen’s “spirituality” has not the least flicker of a longing to “leave Sex behind.” It is bound to Sex, as the insatiable Ghoul is bound to the Corpse he devours. It is not concerned with the physical ecstasies of Sex. It has no interest in such human matters. But deprive it of the fact of Sex-difference, and it drifts away whimpering like a dead leaf, an empty husk, a wisp of chaff, a skeleton gossamer. The poor, actual, warm lips, “so sweetly forsworn,” may have had small interest for this “spiritual” lover, but now that she is dead and buried, and a ghost, they must remain a woman’s lips forever! Nor have Edgar Allen’s “faithful ones” the remotest interest in what goes on around them. Occupied with their Dead, their feeling towards common flesh and blood is the feeling of Caligula. “What have I done to thee?” that proud, reserved face seems to say, as it looks out on us from its dusty title-page; “what have I done to thee, that I should despise thee so?”

Shelley’s clear, erotic passion is always a “cosmic” thing. It is the rhythmic expression of the power that creates the world. But there is nothing “cosmic” about the enclosed gardens of Edgar Allen Poe; and the spirits that walk among those Moon-dials and dim Parterres are not of the kind who go streaming up, from land and ocean, shouting with joy that Prometheus has conquered! But what a master he is—what a master! In the suggestiveness of names—to mention only one thing—can anyone touch him? That word “Porphyrogene”—the name of the Ruler of, God knows what, Kingdom of the Dead—does it not linger about one—and follow one—like the smell of incense?

But the poem of all poems in which the very genius Edgar Allen is embodied is, of course, “Ulalume.” Like this, there is nothing; in Literature—nothing in the whole field of human art. Here he is, from beginning to end, a supreme artist; dealing with the subject for which he was born! That undertone of sardonic, cynical humour—for it can be called nothing else—which grins at us in the background like the grin of a Skull; how extraordinarily characteristic it is! And the touches of “infernal colloquialism,” so deliberately fitted in, and making us remember—many things!—is there anything in the world like them?

“And now as the night was senescent,

And the star-dials hinted of morn,

At the end of our path a liquescent

And nebulous lustre was born,

Out of which a miraculous crescent

Arose with a duplicate horn—

Astarte’s be-diamonded crescent,

Distinct with its duplicate horn!”

“And I said”—but let us pass to his Companion. The cruelty of this conversation with “Psyche” is a thing that may well make us shudder. The implication is, of course, double. Psyche is his own soul; the soul in him which would live, and grow, and change, and know the “Vita Nuova.” She is also “the Companion,” to whom he has turned for consolation. She is the Second One, the Other One, in whose living caresses he would forget, if it might be, that which lies down there in the darkness!

“Then Psyche, uplifting her finger,

Said, ‘sadly this star I mistrust,

Its pallor I strangely mistrust.

O hasten! O let us not linger!

O fly! Let us fly! for we must!'”

Thus the Companion; thus the Comrade; thus the “Vita Nuova”!

Now mark what follows:

“Then I pacified Psyche and kissed her,

And tempted her out of her gloom.

And conquered her scruples and gloom.

And we passed to the end of a Vista,

But were stopped by the door of a Tomb.

By the door of a Legended Tomb,

And I said: ‘What is written, sweet sister,

On the door of this legended Tomb?’

She replied, Ulalume—Ulalume—

Tis the vault of thy lost Ulalume!”

The end of the poem is like the beginning, and who can utter the feelings it excites? That “dark tarn of Auber,” those “Ghoul-haunted woodlands of Weir” convey, more thrillingly than a thousand words of description, what we have actually felt, long ago, far off, in that strange country of our forbidden dreams.

What a master he is! And if you ask about his “philosophy of life,” let the Conqueror Worm make answer:

“Lo! Tis a Gala-Night

Within the lonesome latter years—”

Is not that an arresting commencement? The word “Gala-Night”—has it not the very malice of the truth of things?

Like Heine, it gave this poet pleasure not only to love the Dead, but to love feeling himself dead. That strange poem about “Annie.” with its sickeningly sentimental conclusion, where the poet lies prostrate, drugged with all the drowsy syrops in the world, and celebrates his euthanasia, has a quality of its own. It is the “inverse” of life’s “Danse Macabre.” It is the way we poor dancers long to sleep. “For to sleep you must slumber in just such a bed!” The old madness is over now; the old thirst quenched. It was quenched in a water that “does not flow so far underground.” And luxuriously, peacefully, we can rest at last, with the odour of “puritan pansies” about us, and somewhere, not far off, rosemary and rue!

Edgar Allen Poe’s philosophy of Life? It may be summed up in the lines from that little poem, where he leaves her side who has, for a moment, turned his heart from the Tomb. The reader will remember the way it begins: “Take this kiss upon thy brow.” And the conclusion is the confusion of the whole matter:

“All that we see or seem

Is but a dream within a dream.”

Strangely—in forlorn silence—passes before us, as we close his pages, that procession of “dead, cold Maids.” Ligeia follows Ulalume; and Lenore follows Ligeia; and after them Eulalie and Annabel; and the moaning of the sea-tides that wash their feet is the moaning of eternity. I suppose it needs a certain kindred perversion, in the reader, to know the shudder of the loss, more dear than life, of such as these! The more normal memory of man will still continue repeating the liturgical syllables of a very different requiem:

“O daughters of dreams and of stories,

That Life is not wearied of yet—

Faustine, Fragoletta, Dolores,

Felise, and Yolande and Julette!”

Yes, Life and the Life-Lovers are enamoured still of these exquisite witches, these philtre-bearers, these Sirens, these children of Circe. But a few among us—those who understand the poetry of Edgar Allen—turn away from them, to that rarer, colder, more virginal Figure; to Her who has been born and has died, so many times; to Her who was Ligeia and Ulalume and Helen and Lenore—for are not all these One?—to Her we have loved in vain and shall love in vain until the end—to Her who wears, even in the triumph of her Immortality, the close-clinging, heavily-scented cerements of the Dead!

“The old bards shall cease and their memory that lingers

Of frail brides and faithless shall be shrivelled as with fire,

For they loved us not nor knew us and our lips were dumb, our fingers

Could wake not the secret of the lyre.

Else, else, O God, the Singer,

I had sung, amid their rages,

The long tale of Man,

And his deeds for good and ill.

But the Old World knoweth—’tis the speech of all his ages—

Man’s wrong and ours; he knoweth and is still.”

- A Complete Guide to the Hero’s Journey in Storytelling (Free Worksheet) - April 10, 2025

- On Literary Criticism by Ambrose Bierce - April 9, 2025

- 2025 “Boost Your Happiness” Monthly Haiku Challenge - April 9, 2025