My Thoughts on Walt Whitman by Willa Cather

Introduction to “My Thoughts on Walt Whitman” by Willa Cather

In this thought-provoking essay from 1896, acclaimed American author Willa Cather presents a critical assessment of Walt Whitman’s poetic legacy. Writing for the Nebraska State Journal, Cather examines Whitman’s unconventional approach to poetry with both skepticism and reluctant admiration. She challenges his indiscriminate embrace of all subjects as worthy of poetic treatment while acknowledging the raw vitality that permeates his work. This piece offers valuable insight into how Whitman’s revolutionary style was received by literary contemporaries during the late 19th century, and showcases Cather’s own developing literary voice and critical perspective before she would go on to become one of America’s most celebrated novelists.

My Thoughts on Walt Whitman by Willa Cather

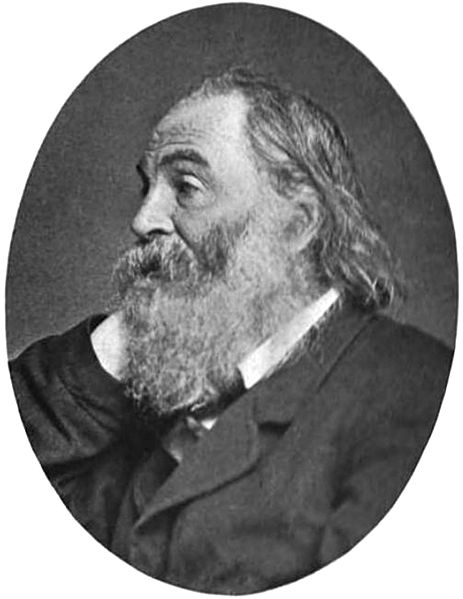

Speaking of monuments reminds one that there is more talk about a monument to Walt Whitman, “the good, gray poet.” Just why the adjective good is always applied to Whitman it is difficult to discover, probably because people who could not understand him at all took it for granted that he meant well. If ever there was a poet who had no literary ethics at all beyond those of nature, it was he. He was neither good nor bad, any more than are the animals he continually admired and envied. He was a poet without an exclusive sense of the poetic, a man without the finer discriminations, enjoying everything with the unreasoning enthusiasm of a boy. He was the poet of the dung hill as well as of the mountains, which is admirable in theory but excruciating in verse. In the same paragraph he informs you that, “The pure contralto sings in the organ loft,” and that “The malformed limbs are tied to the table, what is removed drop horribly into a pail.” No branch of surgery is poetic, and that hopelessly prosaic word “pail” would kill a whole volume of sonnets. Whitman’s poems are reckless rhapsodies over creation in general, some times sublime, some times ridiculous. He declares that the ocean with its “imperious waves, commanding” is beautiful, and that the fly-specks on the walls are also beautiful. Such catholic taste may go in science, but in poetry their results are sad. The poet’s task is usually to select the poetic. Whitman never bothers to do that, he takes everything in the universe from fly-specks to the fixed stars. His “Leaves of Grass” is a sort of dictionary of the English language, and in it is the name of everything in creation set down with great reverence but without any particular connection.

Speaking of monuments reminds one that there is more talk about a monument to Walt Whitman, “the good, gray poet.” Just why the adjective good is always applied to Whitman it is difficult to discover, probably because people who could not understand him at all took it for granted that he meant well. If ever there was a poet who had no literary ethics at all beyond those of nature, it was he. He was neither good nor bad, any more than are the animals he continually admired and envied. He was a poet without an exclusive sense of the poetic, a man without the finer discriminations, enjoying everything with the unreasoning enthusiasm of a boy. He was the poet of the dung hill as well as of the mountains, which is admirable in theory but excruciating in verse. In the same paragraph he informs you that, “The pure contralto sings in the organ loft,” and that “The malformed limbs are tied to the table, what is removed drop horribly into a pail.” No branch of surgery is poetic, and that hopelessly prosaic word “pail” would kill a whole volume of sonnets. Whitman’s poems are reckless rhapsodies over creation in general, some times sublime, some times ridiculous. He declares that the ocean with its “imperious waves, commanding” is beautiful, and that the fly-specks on the walls are also beautiful. Such catholic taste may go in science, but in poetry their results are sad. The poet’s task is usually to select the poetic. Whitman never bothers to do that, he takes everything in the universe from fly-specks to the fixed stars. His “Leaves of Grass” is a sort of dictionary of the English language, and in it is the name of everything in creation set down with great reverence but without any particular connection.

But however ridiculous Whitman may be there is a primitive elemental force about him. He is so full of hardiness and of the joy of life. He looks at all nature in the delighted, admiring way in which the old Greeks and the primitive poets did. He exults so in the red blood in his body and the strength in his arms. He has such a passion for the warmth and dignity of all that is natural. He has no code but to be natural, a code that this complex world has so long outgrown. He is sensual, not after the manner of Swinbourne and Gautier, who are always seeking for perverted and bizarre effects on the senses, but in the frank fashion of the old barbarians who ate and slept and married and smacked their lips over the mead horn. He is rigidly limited to the physical, things that quicken his pulses, please his eyes or delight his nostrils. There is an element of poetry in all this, but it is by no means the highest. If a joyous elephant should break forth into song, his lay would probably be very much like Whitman’s famous “song of myself.” It would have just about as much delicacy and deftness and discriminations. He says:

“I think I could turn and live with the animals. They are so placid and self-contained, I stand and look at them long and long. They do not sweat and whine about their condition. They do not lie awake in the dark and weep for their sins. They do not make me sick discussing their duty to God. Not one is dissatisfied nor not one is demented with the mania of many things. Not one kneels to another nor to his kind that lived thousands of years ago. Not one is respectable or unhappy, over the whole earth.” And that is not irony on nature, he means just that, life meant no more to him. He accepted the world just as it is and glorified it, the seemly and unseemly, the good and the bad. He had no conception of a difference in people or in things. All men had bodies and were alike to him, one about as good as another. To live was to fulfil all natural laws and impulses. To be comfortable was to be happy. To be happy was the ultimatum. He did not realize the existence of a conscience or a responsibility. He had no more thought of good or evil than the folks in Kipling’s Jungle book.

And yet there is an undeniable charm about this optimistic vagabond who is made so happy by the warm sunshine and the smell of spring fields. A sort of good fellowship and whole-heartedness in every line he wrote. His veneration for things physical and material, for all that is in water or air or land, is so real that as you read him you think for the moment that you would rather like to live so if you could. For the time you half believe that a sound body and a strong arm are the greatest things in the world. Perhaps no book shows so much as “Leaves of Grass” that keen senses do not make a poet. When you read it you realize how spirited a thing poetry really is and how great a part spiritual perceptions play in apparently sensuous verse, if only to select the beautiful from the gross.

And yet there is an undeniable charm about this optimistic vagabond who is made so happy by the warm sunshine and the smell of spring fields. A sort of good fellowship and whole-heartedness in every line he wrote. His veneration for things physical and material, for all that is in water or air or land, is so real that as you read him you think for the moment that you would rather like to live so if you could. For the time you half believe that a sound body and a strong arm are the greatest things in the world. Perhaps no book shows so much as “Leaves of Grass” that keen senses do not make a poet. When you read it you realize how spirited a thing poetry really is and how great a part spiritual perceptions play in apparently sensuous verse, if only to select the beautiful from the gross.

Nebraska State Journal, January 19, 1896

Why This Essay Is Important

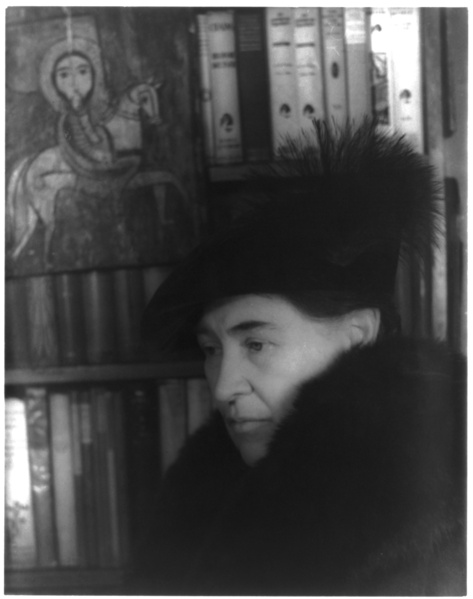

Willa Cather’s critique of Walt Whitman occupies a significant place in American literary history for several compelling reasons. First, it captures the tension between traditional poetic sensibilities and Whitman’s revolutionary, boundary-breaking approach at a pivotal moment in American letters. Cather’s ambivalence—finding Whitman simultaneously “sublime” and “ridiculous”—reflects the broader cultural struggle to come to terms with his radical democratization of poetic subject matter.

Moreover, this essay provides a valuable window into Cather’s own developing literary philosophy before she emerged as a major novelist. Her criticism of Whitman’s lack of selectivity and discrimination foreshadows her own carefully crafted prose style that would later define masterworks like “O Pioneers!” and “My Ántonia.” The essay demonstrates how Cather was already formulating ideas about artistic refinement and the importance of selection that would become hallmarks of her fiction.

Additionally, this document serves as an important artifact in understanding how Whitman’s reputation evolved over time. Writing just four years after Whitman’s death, Cather’s assessment comes at a moment when his legacy was still being contested. Her acknowledgment of his “primitive elemental force” despite her reservations points to the gradual process by which Whitman would eventually be canonized as one of America’s preeminent poets.

Finally, the essay illuminates the intellectual climate of the 1890s, revealing how discussions about nature, modernity, spirituality, and American identity were being negotiated through literary criticism. Cather’s reaction to Whitman’s celebration of the physical world and rejection of conventional morality positions both writers within broader conversations about America’s literary and cultural direction at the turn of the century.

Willa Cather: A Brief Biography

Willa Sibert Cather (1873-1947) was a pioneering American novelist whose work powerfully captured the spirit of the American frontier and immigrant experience. Born in Virginia, Cather moved with her family to Nebraska at age nine, an experience that profoundly shaped her literary vision. The vast prairie landscapes and diverse immigrant communities she encountered there would later become the foundation for her most celebrated works.

After graduating from the University of Nebraska in 1895, Cather worked as a journalist and editor, writing for publications including the Nebraska State Journal and eventually becoming managing editor of McClure’s Magazine in New York. During this period, she honed her critical voice through literary criticism, as evidenced in pieces like her 1896 assessment of Walt Whitman.

Cather published her first novel, “Alexander’s Bridge,” in 1912, but it was her Prairie Trilogy—”O Pioneers!” (1913), “The Song of the Lark” (1915), and “My Ántonia” (1918)—that established her literary reputation. These works featured strong female protagonists and vividly evoked the Nebraska prairie and the struggles of immigrant settlers.

Her 1922 novel “One of Ours” won the Pulitzer Prize, and later works like “Death Comes for the Archbishop” (1927) and “Shadows on the Rock” (1931) further demonstrated her masterful prose style and deep historical imagination. Throughout her career, Cather maintained a distinctive literary vision that valued clarity, precision, and emotional truth while resisting sentimentality.

Though private about her personal life, Cather maintained significant relationships with women, including a decades-long partnership with Edith Lewis. Her work has been increasingly recognized for its subtle exploration of gender roles and identity. By the time of her death in 1947, Cather had secured her place as one of America’s most significant literary voices, creating an enduring body of work that continues to be celebrated for its artistic excellence and cultural insight.

Further Reading on Willa Cather and Walt Whitman

For readers interested in exploring more about Willa Cather, Walt Whitman, and their literary contributions, the following resources offer valuable insights:

Biography and Criticism on Willa Cather

- “Willa Cather: A Literary Life” by James Woodress – The definitive biography exploring Cather’s personal and professional development.

- “The World of Willa Cather” by Mildred Bennett – Examines the Nebraska landscapes and communities that influenced Cather’s fiction.

- “Willa Cather: The Emerging Voice” by Sharon O’Brien – Focuses on Cather’s early career and the development of her literary voice.

- “Willa Cather and the Politics of Criticism” by Joan Acocella – Analyzes changing critical perspectives on Cather’s work across decades.

Walt Whitman Studies

- “Walt Whitman’s America: A Cultural Biography” by David S. Reynolds – Places Whitman in his historical and cultural context.

- “Whitman the Political Poet” by Betsy Erkkila – Examines the political dimensions of Whitman’s poetry.

- “Walt Whitman: The Song of Himself” by Jerome Loving – A comprehensive biography exploring Whitman’s life and work.

Literary History and Context

- “The American 1890s: A Cultural Reader” edited by Susan Harris Smith and Melanie Dawson – Provides context for understanding the literary landscape when Cather wrote her Whitman essay.

- “American Literary Criticism from the Thirties to the Eighties” by Vincent B. Leitch – Includes discussion of how critical perspectives on both Cather and Whitman evolved.

Primary Works

- “Leaves of Grass” by Walt Whitman – The collection Cather critiques in her essay, especially the 1855 and 1891-92 editions.

- “Not Under Forty” by Willa Cather – Cather’s own collection of critical essays that reveals her literary values.

- “The Kingdom of Art: Willa Cather’s First Principles and Critical Statements” edited by Bernice Slote – Collects Cather’s early journalism and criticism, including pieces similar to her Whitman essay.

- On Literary Criticism by Ambrose Bierce - April 9, 2025

- 2025 “Boost Your Happiness” Monthly Haiku Challenge - April 9, 2025

- 87 Gothic Horror Tropes - April 9, 2025