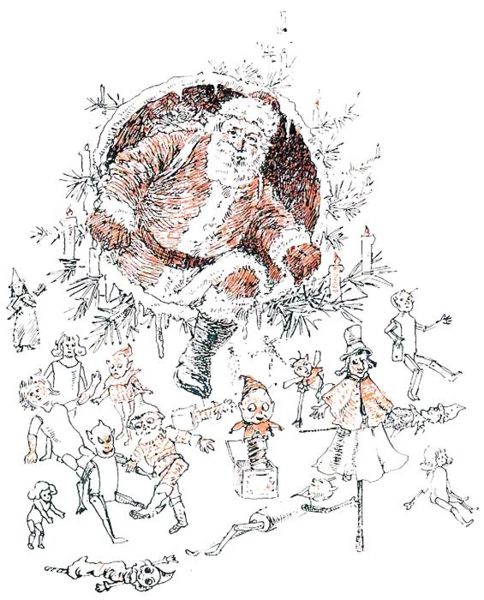

The Christmas Goblins by Charles Dickens

The Christmas Goblins

by Charles Dickens

In an old abbey town, a long, long while ago there officiated as sexton and gravedigger in the churchyard one Gabriel Grubb. He was an ill conditioned cross-grained, surly fellow, who consorted with nobody but himself and an old wicker-bottle which fitted into his large, deep waistcoat pocket.

A little before twilight one Christmas Eve, Gabriel shouldered his spade, lighted his lantern, and betook himself toward the old churchyard, for he had a grave to finish by next morning, and feeling very low, he thought it might raise his spirits, perhaps, if he went on with his work at once.

He strode along until he turned into the dark lane which led to the churchyard a nice, gloomy, mournful place into which the towns-people did not care to go except in broad daylight, consequently he was not a little indignant to hear a young urchin roaring out some jolly song about a Merry Christmas. Gabriel waited until the boy came up, then rapped him over the head with his lantern five or six times to teach him to modulate his voice. And as the boy hurried away, with his hand to his head, Gabriel Grubb chuckled to himself and entered the churchyard, locking the gate behind him.

He took off his coat, put down his lantern, and getting into an unfinished grave, worked at it for an hour or so with right good will. But the earth was hardened with the frost, and it was no easy matter to break it up and shovel it out. At any other time this would have made Gabriel very miserable, but he was so pleased at having stopped the small boy’s singing that he took little heed of the scanty progress he had made when he had finished work for the night, and looked down into the grave with grim satisfaction, murmuring as he gathered up his things:

“Brave lodgings for one, brave lodgings for one,

A few feet of cold earth when life is done.”

“Ho! ho!” he laughed, as he set himself down on a flat tombstone, which was a favorite resting-place of his, and drew forth his wicker-bottle. “A coffin at Christmas! A Christmas box. Ho! ho! ho!”

“Ho! ho! ho!” repeated a voice close beside him.

“It was the echoes,” said he, raising the bottle to his lips again.

“It was not,” said a deep voice.

Gabriel started up and stood rooted to the spot with terror, for his eyes rested on a form that made his blood run cold.

Seated on an upright tombstone close to him was a strange, unearthly figure. He was sitting perfectly still, grinning at Gabriel Grubb with such a grin as only a goblin could call up.

“What do you here on Christmas Eve?” said the goblin, sternly.

“I came to dig a grave, sir,” stammered Gabriel.

“What man wanders among graves on such a night as this?” cried the goblin.

“Gabriel Grubb! Gabriel Grubb!” screamed a wild chorus of voices that seemed to fill the churchyard.

“What have you got in that bottle?” said the goblin.

“Hollands, sir,” replied the sexton, trembling more than ever, for he had bought it of the smugglers, and he thought his questioner might be in the excise department of the goblins.

“Who drinks Hollands alone, and in a churchyard on such a night as this?”

“Gabriel Grubb! Gabriel Grubb!” exclaimed the wild voices again.

“And who, then, is our lawful prize?” exclaimed the goblin, raising his voice.

The invisible chorus replied, “Gabriel Grubb! Gabriel Grubb!”

“Well, Gabriel, what do you say to this?” said the goblin, as he grinned a broader grin than before.

The sexton gasped for breath.

“What do you think of this, Gabriel?”

“It’s…it’s very curious, sir, very curious, sir, and very pretty,” replied the sexton, half-dead with fright. “But I think I’ll go back and finish my work, sir, if you please.”

“Work!” said the goblin, “what work?”

“The grave, sir.”

“Oh! the grave, eh? Who makes graves at a time when other men are merry, and takes a pleasure in it?”

Again the voices replied, “Gabriel Grubb! Gabriel Grubb!”

“I’m afraid my friends want you, Gabriel,” said the goblin.

“Under favor, sir,” replied the horror-stricken sexton, “I don’t think they can; they don’t know me, sir; I don’t think the gentlemen have ever seen me.”

“Oh! yes, they have. We know the man who struck the boy in the envious malice of his heart because the boy could be merry and he could not.”

Here the goblin gave a loud, shrill laugh which the echoes returned twenty-fold.

“I?I am afraid I must leave you, sir,” said the sexton, making an effort to move.

“Leave us!” said the goblin; “ho! ho! ho!”

As the goblin laughed he suddenly darted toward Gabriel, laid his hand upon his collar, and sank with him through the earth. And when he had had time to fetch his breath he found himself in what appeared to be a large cavern, surrounded on all sides by goblins ugly and grim.

“And now,” said the king of the goblins, seated in the centre of the room on an elevated seat his friend of the churchyard?”show the man of misery and gloom a few of the pictures from our great storehouses.”

As the goblin said this a cloud rolled gradually away and disclosed a small and scantily furnished but neat apartment. Little children were gathered round a bright fire, clinging to their mother’s gown, or gamboling round her chair. A frugal meal was spread upon the table and an elbow-chair was placed near the fire. Soon the father entered and the children ran to meet him. As he sat down to his meal the mother sat by his side and all seemed happiness and comfort.

“What do you think of that?” said the goblin.

Gabriel murmured something about its being very pretty.

“Show him some more,” said the goblin.

Many a time the cloud went and came, and many a lesson it taught to Gabriel Grubb. He saw that men who worked hard and earned their scanty bread were cheerful and happy. And he came to the conclusion it was a very respectable sort of a world after all. No sooner had he formed it than the cloud closed over the last picture seemed to settle on his senses and lull him to repose. One by one the goblins faded from his sight, and as the last one disappeared he sank to sleep.

The day had broken when he awoke, and found himself lying on the flat gravestone, with the wicker-bottle empty by his side. He got on his feet as well as he could, and brushing the frost off his coat, turned his face toward the town.

But he was an altered man, he had learned lessons of gentleness and good-nature by his strange adventures in the goblin’s cavern.