The Vanished Mummy by Charles Bump

The Vanished Mummy

by Charles Bump

In the detective headquarters in the Courthouse they have mistakenly built up a very high notion of my sleuth qualities. Personally I have always felt that such help as I have been able to render them in two or three different cases was most largely due to luck, and only in a small degree to the exercise of logic and common sense in making deductions of subsequently proven importance from apparently trivial facts. Nevertheless, the good fortune that attended me in those cases fixed my reputation with them as the Sherlock Holmes of Baltimore, while the generosity with which I permitted them to take all the glory of solving the mysteries made me solid and caused them to consult me the more frequently in hours of perplexity. At the same time, I confess it, the love of the game made me eager to be in it and I not only installed a ‘phone in my apartment in the Arundel, but I was always careful, in absenting myself from my office or my flat, to leave word where I would most likely be found during the next few hours. In this way the puzzled Vidocqs were usually able to reach me when my help was needed.

I was whiling away a rainy Saturday afternoon at the Maryland a few weeks ago when I saw Dorland making signs to me from the passageway behind the boxes on the right of the theatre. Lieutenant Amers’ redcoated British band, of which I had grown very fond, was rendering the final crashing bars of the overture to “Wilhelm Tell,” and, with my passionate love for music, I was loth to leave until the programme was completed. But Dorland was a detective who never came for me unless there was an interesting mystery to offer and I left my seat at once and joined him in the lobby.

“Which way, Dorland?” I asked.

“Woman’s College, sir,” he answered, just as briefly.

I gave an exclamation of surprise. An institution attended by hundreds of girls from the best families of America was not the place one would expect a mystery of crime.

“Very curious case, sir. Mummy of an Egyptian princess stolen.”

“Odd affair,” I remarked. “Gives promise of being most unusual. Any clue?”

“Not a shred, sir.”

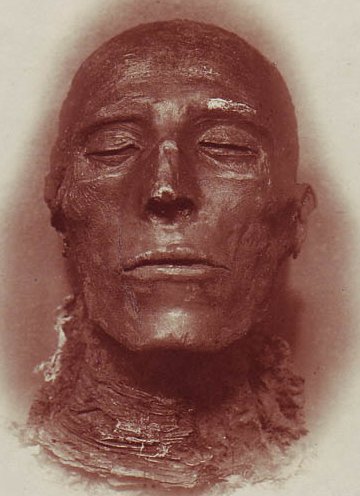

On our way out to the College on a Roland-Park car, Dorland gave me a recital of such facts as he had learned. The mummy had been secured in Egypt with much difficulty by President Goucher and was one of the prized possessions of the College museum. Partly divested of its wrappings of fine linen turned brown with the centuries, the body of this daughter of the Pharaohs had been exhibited in a glass case on the second floor of Goucher Hall, while nearby had been placed the case in which it had rested for ages, a case of wood painted with figures and hieroglyphics that told the rank and virtues of the little lady. The night before at 6 o’clock the mummy had been in its place. In the morning when the janitor’s wife was sweeping she discovered the glass lid prized open and the mummy gone. The night watchman saw nothing, heard nothing.

“And what are your theories?” I asked Dorland, as we passed along Twenty-third street.

“That it was taken to be sold at a good figure to some other museum; that it was taken to be sold back to the College; that it was a students’ prank; or that it was done by girls being initiated into one of the College secret societies.”

When I had been introduced to and cordially welcomed by a trio of anxious College officials, the dean hastened to assure me of their desire to avoid publicity and notoriety.

“Have you questioned any of the girls today?” I asked.

“No,” replied the dean; “it being Saturday, there have been few of them here, and we have sent for none, so that the loss might be kept secret until we determine on the motive.”

A close examination of the empty glass case and its surroundings was fruitless. Nor did questioning of the janitor and his wife elicit anything new.

“You cleaned very thoroughly,” I said to the woman. “What did you do with the sweepings?”

“They’re in a box in the basement, sir.”

At my request the box was brought up. It was a soap box almost full. “Are these only the sweepings of today?” I asked. The janitor spoke up. “I emptied all the others yesterday, sir,” he declared. With this assurance, I plunged my hands into the pile and began a minute and careful search of it, dumping handful after handful on newspapers spread over a table in Dr. Goucher’s office. Dorland kept the others in conversation, and this fortunately enabled me to make a couple of finds unnoticed by them.

At the end of 10 minutes I had reached the bottom of the box. Turning then to the dean, I said:

“How many Canadian students have you here?”

“Canadians? Oh, two?Miss Carothers and Miss Anstey.”

“And may I see them?”

“I cannot see”? began the dean warmly.

I hastened to assure him I had no idea of suspecting them. “Nevertheless,” I added, “I should like to question them. I have a theory that one or the other may help me.”

The dean was mollified. “Miss Carothers has been absent sick for several days. Miss Anstey you can see. She is a charming girl. Her father is one of the leading Methodist divines of Canada, and an old friend of Dr. Goucher and myself. She does not live in the College homes, but with a lady around the corner on Charles street, who is also an old family friend. I will send you there. She may not be at home just now, but you can try.”

The janitor’s wife spoke up, “Miss Anstey was here an hour or so ago, sir. She was upstairs for a few minutes, and then went out and got in an auto with a young gentleman.”

“I will go around to her home at any rate,” I said.

“You have very little hope of finding the mummy, have you not, Mr. McIver?” asked the dean, anxiously.

“On the contrary,” I replied confidently. “I expect to bring back the Egyptian princess in an hour or two.”

He accepted my boast dubiously. “Whatever you do,” he urged, “use no questionable methods, for the sake of the College. If you find the thief, let me decide whether to prosecute him. If you can get back the mummy without injury, I would prefer to hush up the affair.”

I promised him I would. “I consider this a very unusual case,” I said, “and I believe you will be satisfied with my disposition of it.” With this I left him.

Dorland and the College professor who accompanied us were both eager to know what clue I had, but I stood them off as we walked round to the Charles-street dwelling.

Miss Anstey was out, as I had anticipated, but we were graciously received by Mrs. Eden, her hostess. It was a home of culture and refinement, and the large parlor abounded in paintings, art objects and other curios evidently picked up in foreign travel. “I expect Ethel home soon,” said the sweet-faced and sweet-voiced old lady. “She went motoring this afternoon with a friend, and she said she would be home to supper.”

“We called to ask,” I remarked, “whether she had not lost this bit of jewelry.” And to the surprise of Dorland and the professor I produced a pin I had found in the sweepings of Goucher Hall, a tiny enameled maple leaf, set around with pearls.

“Yes, that is Ethel’s!” exclaimed Mrs. Eden. “I don’t think she lost it, however, for she had recently loaned it to a friend.” She smiled. “You know, young girls nowadays have a great habit of exchanging tokens like this with young men. It was not so in my day.”

“And if I be not rude,” I continued, “may I not know the name of this young man?”

“Why, certainly,” replied the lady. “He is Mr. Raymond Harding.”

“You mean,” I inquired, “the son of Mr. Harding, the bank president?” The Hardings, as everybody knows, are among the best-known millionaire families in Baltimore society.

“The same,” replied Mrs. Eden. “Miss Anstey and he have been friends for a couple of years. I am sure both will be grateful to you for finding this pin. Now that I recall it, it may be that they have already had words about it being lost. He was here last evening and they were both rather excited. At breakfast Ethel complained of having a headache and looked as though she had been crying. They called each other up several times by ‘phone during the morning, but Ethel told me nothing, and I thought it tactful to say nothing to her. When he came this afternoon I told her she looked so pale she ought to rest, but she laughed me off.”

“We will come again after they have returned,” I said to Mrs. Eden as I rose to go. “Perhaps, as you say, I may be able to straighten out the little trouble. Meanwhile, I would suggest that you say nothing to them.”

It had grown dark when we stepped outside. Dorland gripped my hand warmly. “McIver,” he exclaimed, “you’re a wonder! I see the whole case now. Gee, but its a rum affair!”

The professor was mystified. “I don’t quite see, gentlemen, how the whole affair is settled. Where is the mummy? And who was the thief?”

“The mummy, professor,” I remarked, oracularly, “is most probably in the automobile of Mr. Raymond Harding.”

“You don’t mean that he is the thief?”

“I believe he took the mummy. I believe he dropped the pin in doing it. This also fell out of his auto cap.” I produced a gilt paper initial “H,” such as hatters put in headwear for their customers. It was my second find in the sweepings.

“But the motive, man, the motive!” persisted the professor. “Why should a millionaire’s son break into a Woman’s College building to steal a mummy? It sounds ridiculous.”

“That, sir, is the part I want Miss Anstey to explain. It is the only element of doubt in a perfectly plain chain of circumstances. Raymond Harding I know slightly, and he has a certain reputation for reckless pranks, although he’s not a bad fellow.”

“But surely you don’t suspect Ethel Anstey. Why, man, she’s a”

The mournful notes of a Gabriel’s horn down at Twenty-second street betokened the approach of an auto, and interrupted the professor’s eulogium of one who was manifestly a favorite pupil. “Quick!” I exclaimed; “saunter to the corner.” A big touring car came up Charles street and stopped in front of the Eden home. A slender young chap stepped out and aided a young lady to descend. They stood for a minute on the curb beside the machine undecided, as I figured out, whether the mummy would be safe there if left alone and then both passed into the house.

The three of us with one accord moved down the pavement. “Look on the rear seat, Dorland,” I said, as the headquarters man ran to the auto. A great part of my confidence in my well-developed solution of the mystery would have gone to smash if the mummy had not been there. But Dorland gave a little cry of triumph. “It’s here, all right,” he called, “wrapped up in a rubber blanket.” We tried to lift the bundle, but the petrified daughter of the Pharaohs was heavier than he had calculated. “Be careful, Mr. Dorland,” the professor entreated; “don’t smash her.”

“Now for the young man,” said Dorland, jumping down to the curb.

“No,” said I. “I have a better plan. Can you run an auto?”

Dorland could.

“And have you a key to Goucher Hall?” I asked the professor.

The professor had.

“Then you two quietly take the mummy back to her box while I go in and question Miss Anstey.”

They got off without fuss, and when I had seen them turn the corner I rang the bell and asked for Miss Anstey. In placing my hat on the hallrack I moved Harding’s cap to another peg and observed, as I had thought, that the “H” had parted company with the other gilt initials.

I felt unfeignedly sorry for the girl when she came into the parlor a few minutes later. She had fine regular features, and with her limpid blue eyes was unquestionably pretty when the flush of youth and vivacity had full play. But that day there were dark circles under her eyes, her lids were suspiciously red and there was a pallid hue in her cheeks that was accentuated by the dark blue silk suit she wore. A novice at reading character could have told she had been spending hours in worry and tears.

“You wished to see me?” she said, inquiringly, as she slowly advanced to where I had risen to meet her.

“To return this,” I answered. And I held out the maple leaf pin to her.

She grew, if possible, more white and sought the help of the piano to support herself.

“I..?It is not. Where did you get it?” she said, with several gulps to keep down the sobs.

“It was found in Goucher Hall near the mummy case.”

She stepped back uncertainly. Then she pulled herself together.

“You are a detective?”

I winced. “No,” I said; “I am a friend of the College and of Mr. Harding’s.”

At the mention of his name she broke down completely and, sinking on the stool, leaned her head and began to cry. “Oh, Raymond!” I heard her say. “It means disgrace. It means the penitentiary.” Her form shook violently with her emotion. It was more than I could stand.

“Listen, Miss Anstey,” I said, and I laid my hand lightly on her shoulder. “It means nothing of the kind. You have my word as a gentleman that no one shall know the story save the two or three who already know it.”

She lifted her tear-stained face and studied me earnestly. “It was a mad prank,” she sobbed. “I am to blame. I ought to be punished. It started as a joke. I had no idea he’d do it.”

“Call Raymond down.”

She went out into the hallway and a whistled signal brought Harding to us. When he entered the parlor his surprise at seeing me was great.

“He knows about the mummy,” said the girl faintly.

Harding stepped away from us both. “He knows?”

“Yes, he wants to help us.”

“I want to get you out of a nasty scrape, Raymond,” I remarked.

The boy eyed me intently. Then he put out his hand and gripped mine. “Thank you, McIver,” he said, simply. And the three of us sitting down, the boy and the girl told me the whole truth about the kidnapping of the Egyptian princess. Each supplied parts of the narrative. Raymond, I learned, had prized open the case on a visit to the College museum on Friday afternoon and had then secreted himself in the building. When the watchman was in a remote corner, it had taken but a minute to lift the mummy, carry it downstairs, unlock the north door and slip out to where he had left his auto. “Then he came here to show it to me,” said Miss Anstey. “And then I went to take it back,” pursued the boy. “And, Lord, McIver, I found the watchman had locked the door. Ever since then we’ve been in an awful fright. I didn’t know what to do with the bloody thing.”

“What on earth made you take it?” I asked.

The boy turned a troubled eye on the girl. “I did it on a dare,” he said after a pause.

A rosy flush had replaced her pallor. “That isn’t the whole truth, Mr. McIver,” she said. “There was a wager, and a lot of teasing, and talk about a kiss. It sounds so silly now, but it was all in fun. I didn’t expect him to do it. And, oh! how sorry I am!”

“The question is, McIver,” said the boy, “how on earth am I to get it back.”

“That’s the easiest part,” I said. “In fact, it is already back.” I paused to enjoy their pleased surprise. “And if I mistake not here are the two gentlemen that did it.” The doorbell had rung and I stepped out to admit Dorland and the professor.

The next 15 minutes was a medley of questions, of explanations, of promises to keep mum and of expressions of heartfelt thanks from the young couple. The professor was the only one who thought it incumbent to scold them for a silly prank and to point out the serious danger in which they had been involved. It sobered them, and at the same time it made them realize what a tremendous service I had done them.

One point puzzled Dorland. When we had left the house and parted from the professor, he asked me:

“How on earth did you know that pin was Miss Anstey’s?”

“Had it been a thistle design,” I said, “I should have begun a search for that ‘bonnie sweet lass, the Maid o’ Dundee.”

“I don’t exactly see,” he ejaculated.

“The maple leaf, my son, is the national emblem of Canada.”

“Ah,” said Dorland, “that’s what you get by book-larnin’.”

“Yes,” I admitted; “it helps some.”