What I Think of These Three Writers

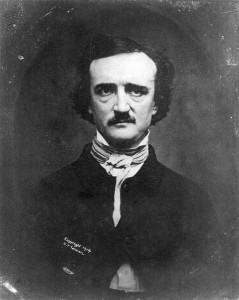

by Edgar Allen Poe

OF WILLIS, BRYANT, HALLECK, AND MACAULAY

Whatever may be thought of Mr. Willis’s talents, there can be no doubt about the fact that, both as an author and as a man, he has made a good deal of noise in the world—at least for an American. His literary life, in especial, has been one continual emeute; but then his literary character is modified or impelled in a very remarkable degree by his personal one. His success (for in point of fame, if of nothing else, he has certainly been successful) is to be attributed one-third to his mental ability and two-thirds to his physical temperament—the latter goading him into the accomplishment of what the former merely gave him the means of accomplishing…. At a very early age, Mr. Willis seems to have arrived at an understanding that, in a republic such as ours, the mere man of letters must ever be a cipher, and endeavored, accordingly, to unite the eclat of the litterateur with that of the man of fashion or of society. He “pushed himself,” went much into the world, made friends with the gentler sex, “delivered” poetical addresses, wrote “scriptural” poems, traveled, sought the intimacy of noted women, and got into quarrels with notorious men. All these things served his purpose—if, indeed, I am right in supposing that he had any purpose at all. It is quite probable that, as before hinted, he acted only in accordance with his physical temperament; but, be this as it may, his personal greatly advanced, if it did not altogether establish his literary fame. I have often carefully considered whether, without the physique of which I speak, there is that in the absolute morale of Mr. Willis which would have earned him reputation as a man of letters, and my conclusion is that he could not have failed to become noted in some degree under almost any circumstances, but that about two-thirds (as above stated) of his appreciation by the public should be attributed to those adventures which grew immediately out of his animal constitution.

Whatever may be thought of Mr. Willis’s talents, there can be no doubt about the fact that, both as an author and as a man, he has made a good deal of noise in the world—at least for an American. His literary life, in especial, has been one continual emeute; but then his literary character is modified or impelled in a very remarkable degree by his personal one. His success (for in point of fame, if of nothing else, he has certainly been successful) is to be attributed one-third to his mental ability and two-thirds to his physical temperament—the latter goading him into the accomplishment of what the former merely gave him the means of accomplishing…. At a very early age, Mr. Willis seems to have arrived at an understanding that, in a republic such as ours, the mere man of letters must ever be a cipher, and endeavored, accordingly, to unite the eclat of the litterateur with that of the man of fashion or of society. He “pushed himself,” went much into the world, made friends with the gentler sex, “delivered” poetical addresses, wrote “scriptural” poems, traveled, sought the intimacy of noted women, and got into quarrels with notorious men. All these things served his purpose—if, indeed, I am right in supposing that he had any purpose at all. It is quite probable that, as before hinted, he acted only in accordance with his physical temperament; but, be this as it may, his personal greatly advanced, if it did not altogether establish his literary fame. I have often carefully considered whether, without the physique of which I speak, there is that in the absolute morale of Mr. Willis which would have earned him reputation as a man of letters, and my conclusion is that he could not have failed to become noted in some degree under almost any circumstances, but that about two-thirds (as above stated) of his appreciation by the public should be attributed to those adventures which grew immediately out of his animal constitution.

Mr. Bryant’s position in the poetical world is, perhaps, better settled than that of any American. There is less difference of opinion about his rank; but, as usual, the agreement is more decided in private literary circles than in what appears to be the public expression of sentiment as gleaned from the press. I may as well observe here, too, that this coincidence of opinion in private circles is in all cases very noticeable when compared with the discrepancy of the apparent public opinion. In private it is quite a rare thing to find any strongly-marked disagreement—I mean, of course, about mere authorial merit…. It will never do to claim for Bryant a genius of the loftiest order, but there has been latterly, since the days of Mr. Longfellow and Mr. Lowell, a growing disposition to deny him genius in any respect. He is now commonly spoken of as “a man of high poetical talent, very ‘correct,’ with a warm appreciation of the beauty of nature and great descriptive powers, but rather too much of the old-school manner of Cowper, Goldsmith and Young.” This is the truth, but not the whole truth. Mr. Bryant has genius, and that of a marked character, but it has been overlooked by modern schools, because deficient in those externals which have become in a measure symbolical of those schools.

The name of Halleck is at least as well established in the poetical world as that of any American. Our principal poets are, perhaps, most frequently named in this order—Bryant, Halleck, Dana, Sprague, Longfellow, Willis, and so on—Halleck coming second in the series, but holding, in fact, a rank in the public opinion quite equal to that of Bryant. The accuracy of the arrangement as above made may, indeed, be questioned. For my own part, I should have it thus—Longfellow, Bryant, Halleck, Willis, Sprague, Dana; and, estimating rather the poetic capacity than the poems actually accomplished, there are three or four comparatively unknown writers whom I would place in the series between Bryant and Halleck, while there are about a dozen whom I should assign a position between Willis and Sprague. Two dozen at least might find room between Sprague and Dana—this latter, I fear, owing a very large portion of his reputation to his quondam editorial connection with The North American Review. One or two poets, now in my mind’s eye, I should have no hesitation in posting above even Mr. Longfellow—still not intending this as very extravagant praise…. Mr. Halleck, in the apparent public estimate, maintains a somewhat better position than that to which, on absolute grounds, he is entitled. There is something, too, in the bonhomie of certain of his compositions—something altogether distinct from poetic merit—which has aided to establish him; and much also must be admitted on the score of his personal popularity, which is deservedly great. With all these allowances, however, there will still be found a large amount of poetical fame to which he is fairly entitled…. Personally he is a man to be admired, respected, but more especially beloved. His address has all the captivating bonhomie which is the leading feature of his poetry, and, indeed, of his whole moral nature. With his friends he is all ardor, enthusiasm and cordiality, but to the world at large he is reserved, shunning society, into which he is seduced only with difficulty, and upon rare occasions. The love of solitude seems to have become with him a passion.

Macaulay has obtained a reputation which, altho deservedly great, is yet in a remarkable measure undeserved. The few who regard him merely as a terse, forcible and logical writer, full of thought, and abounding in original views, often sagacious and never otherwise than admirably exprest—appear to us precisely in the right. The many who look upon him as not only all this, but as a comprehensive and profound thinker, little prone to error, err essentially themselves. The source of the general mistake lies in a very singular consideration—yet in one upon which we do not remember ever to have heard a word of comment. We allude to a tendency in the public mind toward logic for logic’s sake—a liability to confound the vehicle with the conveyed—an aptitude to be so dazzled by the luminousness with which an idea is set forth as to mistake it for the luminousness of the idea itself. The error is one exactly analogous with that which leads the immature poet to think himself sublime wherever he is obscure, because obscurity is a source of the sublime—thus confounding obscurity of expression with the expression of obscurity. In the case of Macaulay—and we may say, en passant, of our own Channing—we assent to what he says too often because we so very clearly understand what it is that he intends to say. Comprehending vividly the points and the sequence of his argument, we fancy that we are concurring in the argument itself. It is not every mind which is at once able to analyze the satisfaction it receives from such essays as we see here. If it were merely beauty of style for which they were distinguished—if they were remarkable only for rhetorical flourishes—we would not be apt to estimate these flourishes at more than their due value. We would not agree with the doctrines of the essayist on account of the elegance with which they were urged. On the contrary, we would be inclined to disbelief. But when all ornament save that of simplicity is disclaimed—when we are attacked by precision of language, by perfect accuracy of expression, by directness and singleness of thought, and above all by a logic the most rigorously close and consequential—it is hardly a matter for wonder that nine of us out of ten are content to rest in the gratification thus received as in the gratification of absolute truth.

- 100 Must-Try Mystery Writing Prompts (Solve the Perfect Crime!) - March 22, 2025

- Ultimate World-Building Guide: Create Immersive Fictional Universes - March 19, 2025

- How to Overcome Writer’s Block: 5 Proven Strategies (+ Free Worksheet) - March 17, 2025